As discussions surrounding tariffs circulate through the news, it is important to understand what they are and how they work. Tariffs are taxes that are imposed by governments on goods and services imported from other countries. The primary intent of tariffs is to raise the price of imported goods relative to domestically produced goods, so that national commodities have a competitive price advantage. Tariffs are a form of protectionist policy and are often employed to protect emerging and strategic industries and to preserve domestic labor opportunities. In rare circumstances, tariffs can be used as a penalty or in retaliation against other countries. This post serves to illustrate the economic impact of tariffs using the most delicious Utah commodity, fry sauce.

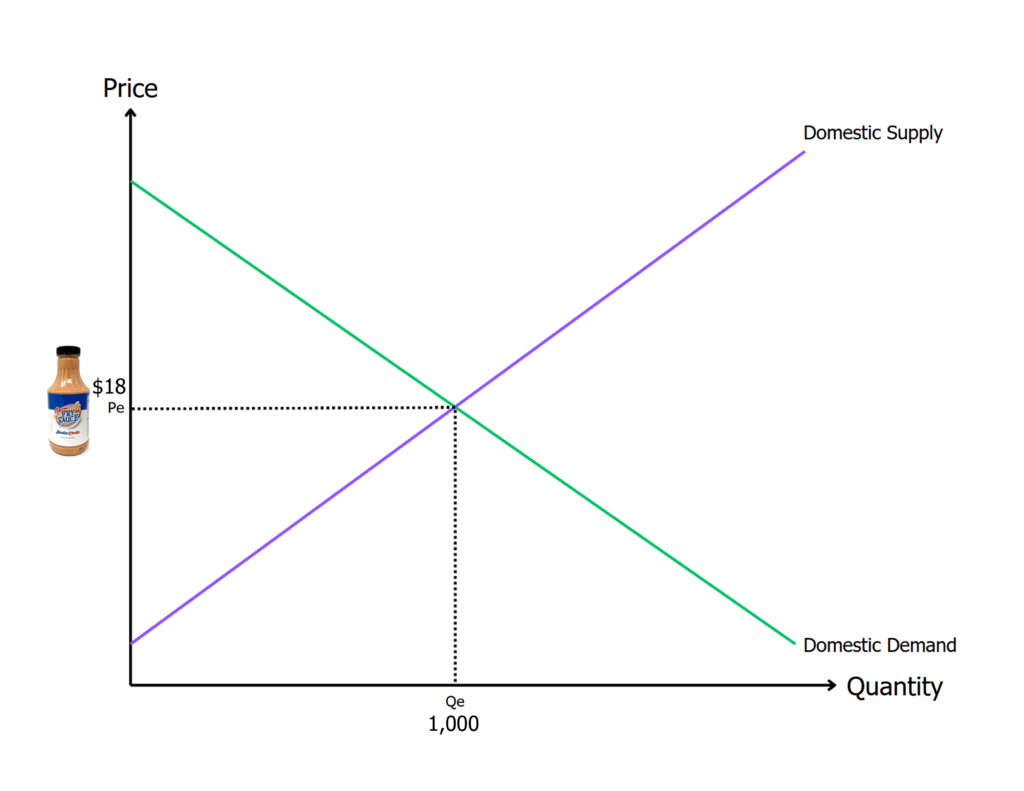

To investigate how tariffs shift supply and demand, we first need to start with a market that doesn’t allow trade. We can see on the chart below that a market in equilibrium without trade will have its Price (Pe) and Quantity (Qe) set where domestic demand intersects domestic supply. Let’s say this is the market for fry sauce, a Utah classic. In this instance, Pe could be $18 for a bottle of Utah-made Arctic Circle Fry Sauce, and Qe is 1,000.

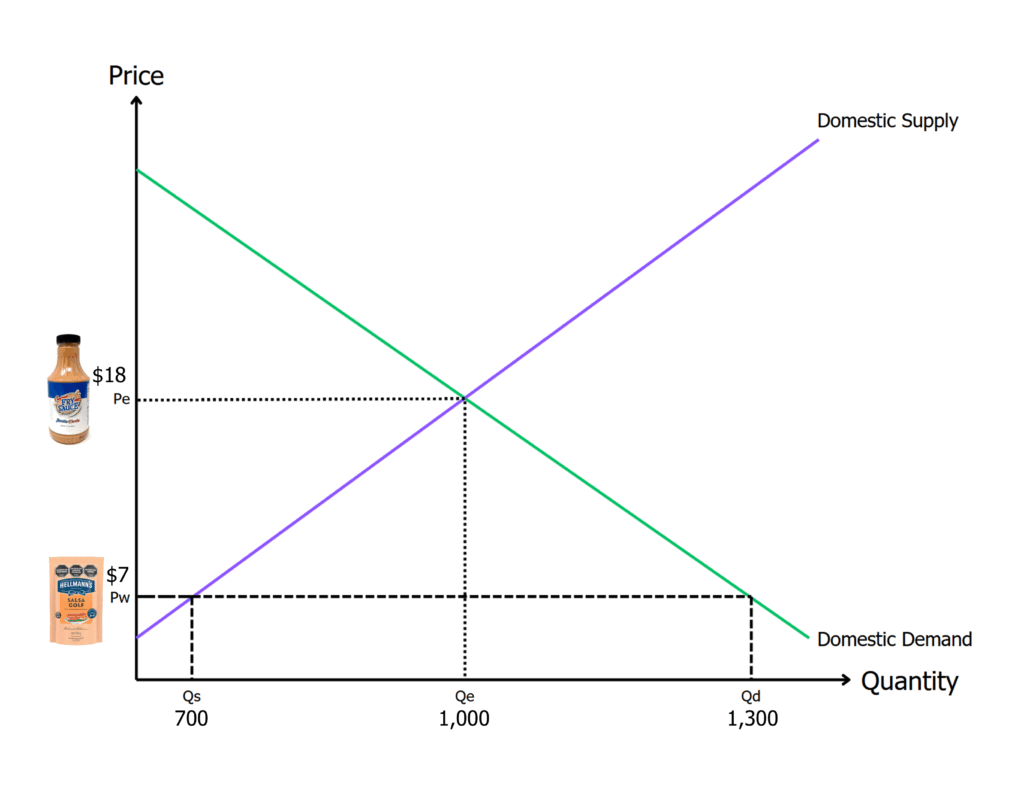

When we allow for international trade in the Utah condiment market, we find that the World Price (Pw) is typically well below $18. This is because we are opening our consumption up to a much larger market comprised of businesses who in many cases are more efficient at producing fry sauce. We can see on the second diagram below that when including global products, the competitive price would drop from Pe to Pw, creating a divergence in the domestically produced quantity (Qs) and the domestic demand (Qd) at this lower price. The difference between Qs and Qd is made up by imports. Returning to our sauce analogy, if Pe is $18, Pw is the equivalent of importing golf sauce from Argentina at $7. (Golf sauce, or salsa golf, is mayo and ketchup-based sauce that for the purposes of this analogy can act as a perfect substitute for fry sauce.) Because so many people switch to buying the cheaper sauce, Utah manufacturers would start being priced out. This would result in domestic production dropping from 1,000 at Qe to 700 at Qs. However, with the new, lower price, domestic demand would rise from 1,000 at Qe to 1,300 at Qd.

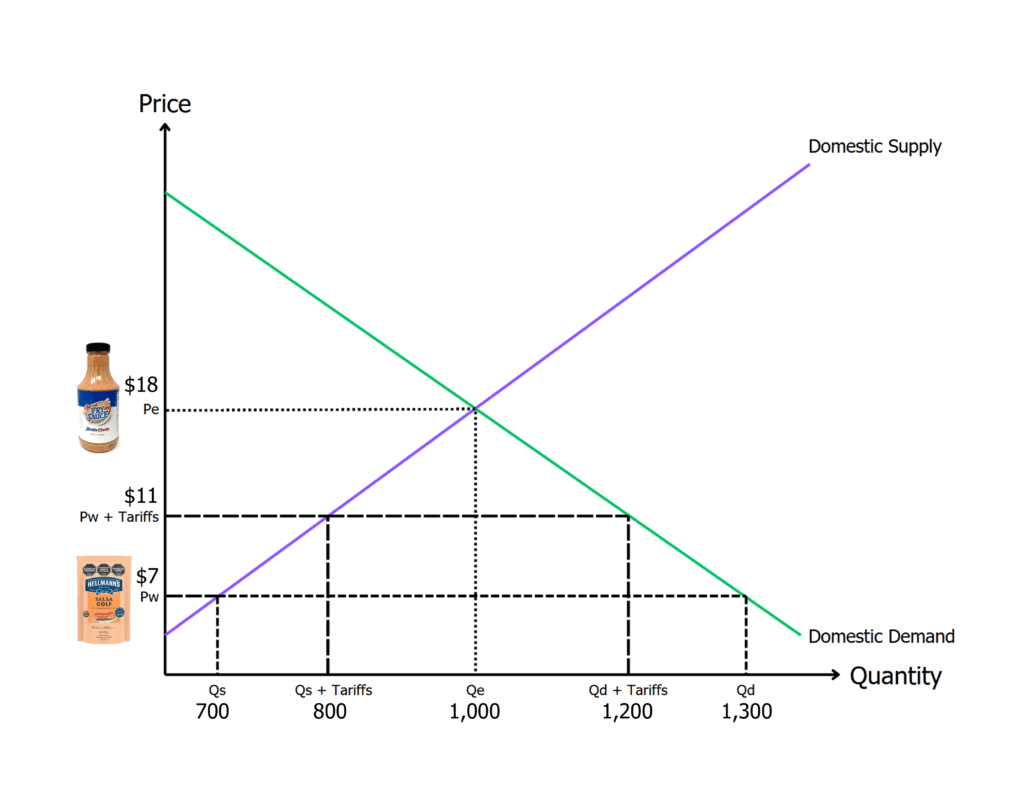

At this point in the sauce shortage, a tariff could be introduced to help bring domestic supply in line with demand. In the third chart below, the impact of introducing a tariff raises the price to Pw + Tariffs (the world price plus the tariff). In our example, Utah could choose to put a $4 per bottle tariff on imported fry sauce, increasing the price to $11. That would increase domestically supplied fry sauce from Qs at 700 to Qs + Tariffs at 800. This would, however, also drop domestic demand for fry sauce from Qd at 1,300 to Qd + Tariffs at 1,200. The impact of the tariff being 200 additional units that are produced in Utah rather than being imported.

Based on this model, we could theoretically see a resurgence in fry sauce in Utah, which may have jobs associated with the increased condiment production. We can also see that a tariff could have an artificial inflationary effect on a market since the price increased by 57% from Pw ($7) to Pw + Tariffs ($11).

It is important to note, however, that when a tariff is announced, it is often announced as being levied against another country; however, this can be misleading because the country that has the tariff levied against it never pays the tariff. Depending on how long the tariff is in effect, the additional cost could either be absorbed by a company to keep prices consistent or it could be passed on to the consumer. In this way, tariffs essentially act as a tax on consumption, predominantly affecting anyone who purchases imported goods.

In the United States, tariffs are collected by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which operates under the authority of the Department of Homeland Security but enforces trade laws and regulations on behalf of the U.S. Department of Commerce. Typically, CBP officers assess and collect tariffs and duties at ports of entry when goods cross the border. Historically, U.S. tariffs have varied significantly depending on the economic or political climate. However, in recent years, the United States has embraced more free trade principles, including entering into agreements like those organized by the World Trade Organization and pacts like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) (now the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, USMCA). These trade agreements meant that the U.S. has averaged tariffs of 2.2% until recently. Additionally, since about 1945, tariff revenue has comprised only about 2% of the total U.S. federal revenue.