In the field of structural engineering, a stress test is not a prediction of failure, but a verification of resilience. Engineers apply hypothetical, extreme loads to ensure that even under the worst possible conditions, the structure remains sound. Since 2018, Utah has applied this same rigorous examination to its financial foundation. UCA 36-12-13 requires legislative economists to conduct a comprehensive budget stress test in a three-year cycle as part of a package of long-term fiscal health analyses. The stress test aims to answer a fundamental question: if the economy were to take a turn, does the state have enough reserves to keep the lights on without cutting essential services or raising taxes?

The recently released 2025 Update (FY 2026 Stress Test) represents the third iteration of this exercise. The findings offer a nuanced look at a state budget that is both more prosperous and more exposed than it was during the last major check-up in 2022. As a result, while the state’s total reserves have grown significantly, the Value at Risk has also climbed. In contrast to this post from October, which examined the value of contingencies invested in gold, the stress test reviews the relationship between total reserves and the ability to utilize those assets in various economic downturns. The punchline from the FY 2026 Stress Test is a recommendation from legislative economists for proactive rebalancing between buffers of varying accessibility.

The $7.5 Billion Structural Load

The central metric of the stress test is the Value at Risk (VaR). This figure combines two factors: the revenue the state might expect to lose due to a contracting economy and the extra money that the state might have to spend on countercyclical programs (i.e. programs that require more resources when the economy slows, like Medicaid). In the 2022 report, the five-year VaR for a severe recession was estimated at $5.6 billion. The 2025 update shows that this risk has expanded to approximately $7.5 billion. This 34% increase in potential risk is driven by several factors, but none is more significant than the inherent volatility of the Income Tax Fund.

Economists identify the Income Tax Fund as the source of 75% of the revenue at risk. Because this fund is heavily influenced by corporate profits and non-wage personal income (such as capital gains), it acts as a highly sensitive barometer for the broader economy. When the market swings, this fund swings harder.

In addition to these changing dynamics inherent to the budget, building on improvements made in the Long-Term Budget, the FY 2026 Stress Test employs a more rigorous methodology than the 2022 report. Previously, a “flat baseline” was used for the final years of the five-year window. The new report uses a “forecasted baseline,” which accounts for expected growth that would be lost during a downturn. This change provides a more realistic—and more sobering—look at the true cost of an economic contraction, ensuring that policymakers are not lulled into a false sense of security by outdated modeling techniques.

The Reinforcements

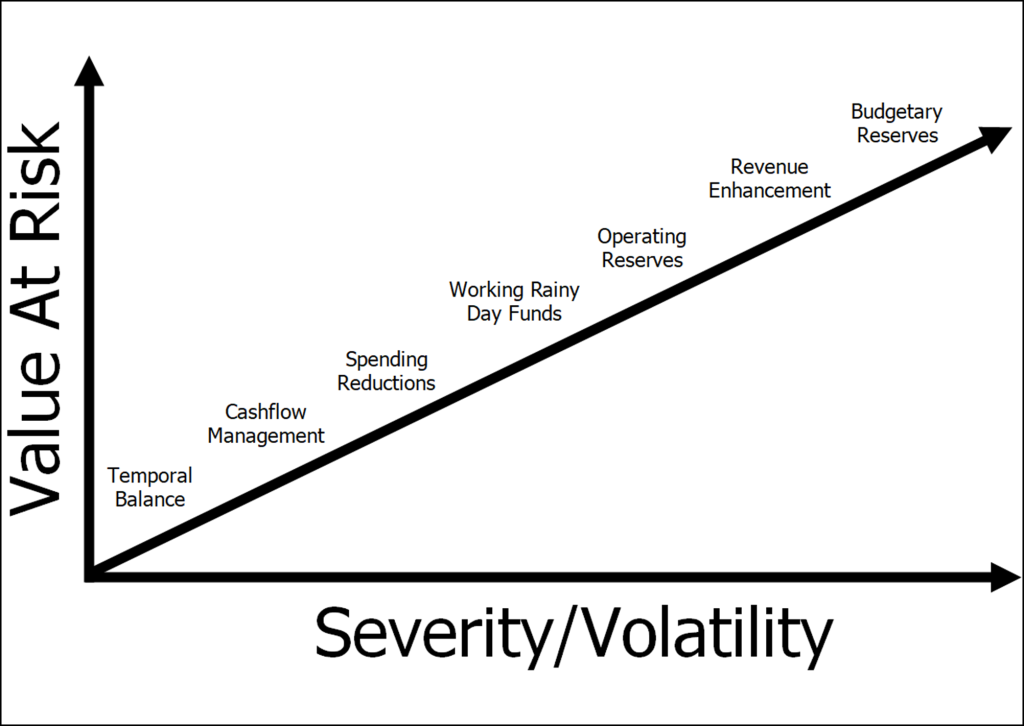

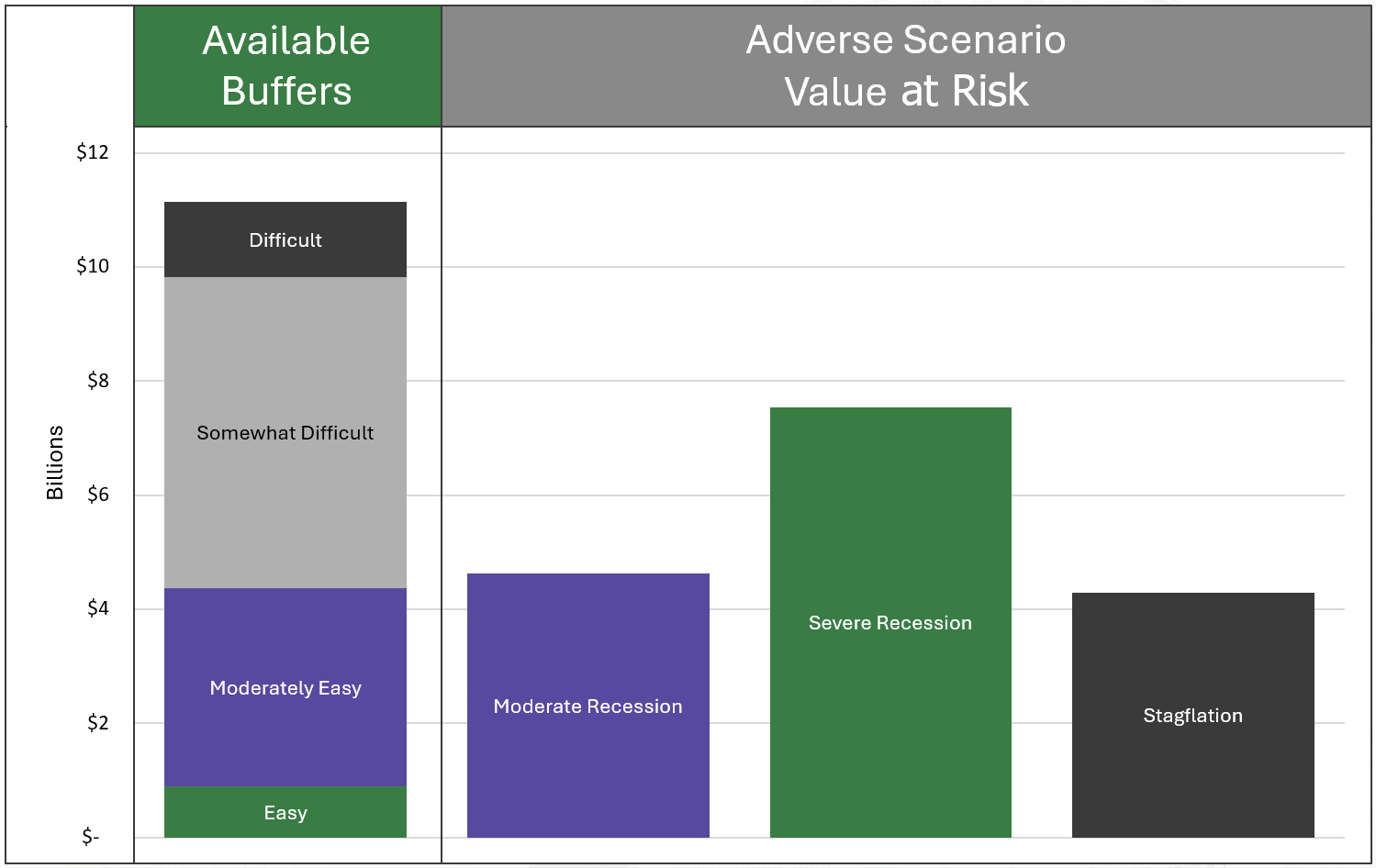

To counter a $7.5 billion risk, Utah maintains an inventory of budget buffers totaling $11.1 billion, up from $9.2 billion in the 2022 report. However, economists emphasize that not all buffers are created equal. Budget contingencies are incorporated into Utah’s Fiscal Toolkit based on how quickly and easily they can be deployed during a crisis.

This categorization is essential because a reserve that requires a constitutional amendment to access is less useful in a fiscal crisis than an ongoing appropriation that can be redirected by a legislative vote. Apart from revenue enhancement (i.e. increasing taxes), the accessibility of the state’s budget contingencies roughly align with the severity of an economic downtown, where more difficult buffers would only be required in the direst of financial situations.

Mapping that same continuum of use from the fiscal toolkit onto the buffers, translating this conceptual framework into actual dollars available, the state’s inventory is currently divided into four tiers based on accessibility:

- Easy-to-Access: includes cash funded infrastructure appropriations, the so-called “working rainy day funds” which could be redirected and postponed or substituted through debt without disrupting core government operations; it also includes certain restricted accounts for Medicaid, which are designed specifically for immediate use during a revenue shortfall.

- Moderately Easy: primarily includes certain one-time fund balances which may be swept during a downturn as well as the ongoing funding for Public Education Economic Stabilization.

- Somewhat Difficult: consists of additional one-time fund balances which have more restrictive parameters for their use and certain ongoing funds which would require statutory change to access, such as earmarked state sales & use tax collections.

- Difficult: includes constitutional reserves, such as the General Fund and Income Tax Fund Budget Reserve Accounts (the state’s formal rainy day funds), which have strict statutory limits on how and when the money can be spent.

This year’s stress test confirms that Utah’s total toolkit is more than sufficient to cover the up to $7.5 billion risk in every modeled scenario, including a severe recession or a period of stagflation (high inflation paired with low growth). However, economists also notes a key shift in the composition of these buffers: while the total amount of money in the toolkit has increased, the percentage of that money classified as Easy-to-Access has declined relative to the total risk.

The Retrofit

Because the state has spent several years utilizing cash for significant infrastructure investments (to avoid long-term debt) the most liquid portion of the state’s reserves has become a smaller share of the whole. In even a moderate recession, the state would likely exhaust Easy-to-Access and Moderately Easy-to-Access buffers almost immediately. To cover the remaining gap, policymakers would be forced to tap into the more difficult to access categories, which could involve halting major construction projects or navigating complex political hurdles.

By identifying this trend ahead of a downturn, policymakers have the opportunity to adjust the trajectory for budget contingencies. The FY 2026 Stress Test suggests that focusing on rebuilding easily accessed buffers in the coming budget cycle will provide increased flexibility for future legislatures. This forward-looking approach is what has historically prevented Utah from being forced into reactive, across-the-board cuts during lean years. In other words, inspecting fiscal footings today ensures the state has breathing room to navigate the uncertainties of tomorrow.