AboutLFAlfastaff

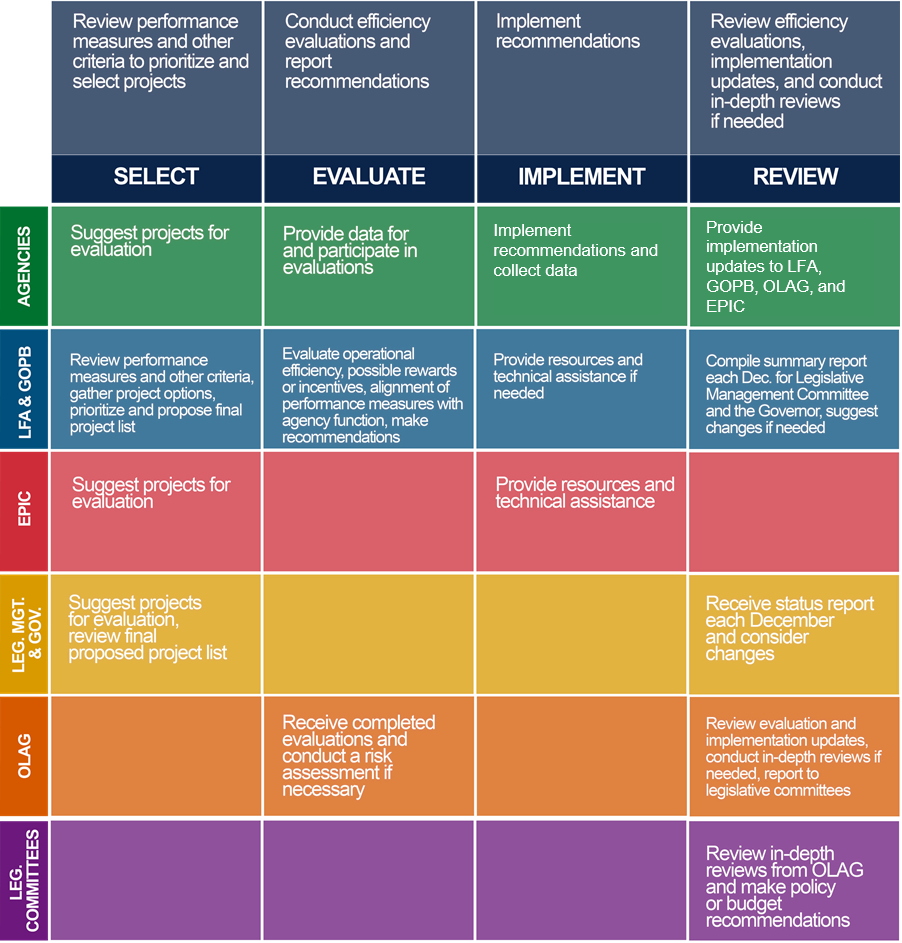

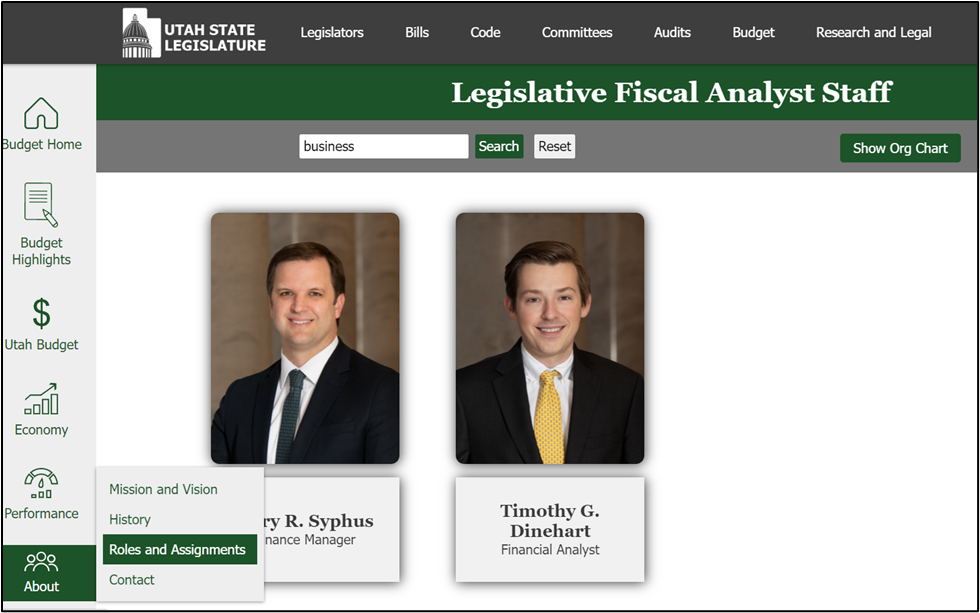

Roles and Assignments

View the LFA's current staff of financial experts, economists, and operations analysts here. You can search by name, subject area, subcommittee, or product. You can also view and organization chart to see the full staff in one place.

Contact

Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst

House Building, Suite W310

Salt Lake City, UT 84114

Ph: (801) 538-1034

AboutLFAofficeoverview

Mission and Vision

The Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst finds sound financial solutions that make Utah better.

History

The Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst was formally established in 1965. Utah has had three Legislative Fiscal Analysts since then, and the office's mission has grown to include budgeting, fiscal health, and performance accountability. Read the full history, here.

AboutLFAproducts

Publications Archive

View all LFA reports, briefs, and publications here. These reports can be filtered by year, type, and committee.

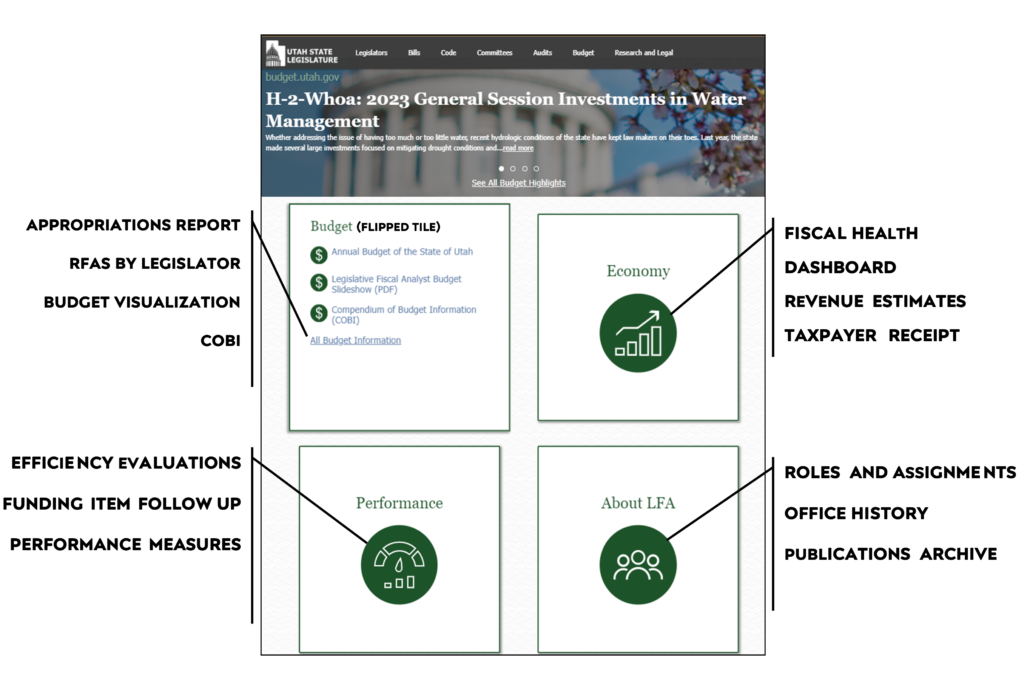

Budgetingappropriations

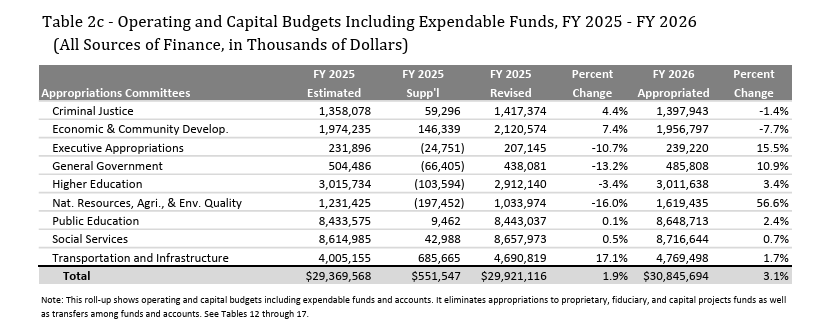

Budget of the State of Utah

This comprehensive report provides a snapshot of legislative budget actions and the state's financial condition. Statute requires the Legislative Fiscal Analyst to complete the report annually.

Utah Budget Quick Facts Card

This pocket-sided summary provides a snapshot of legislative budget actions during the most recent general session (occasionally, this is updated during significant special sessions).

Appropriations Bills

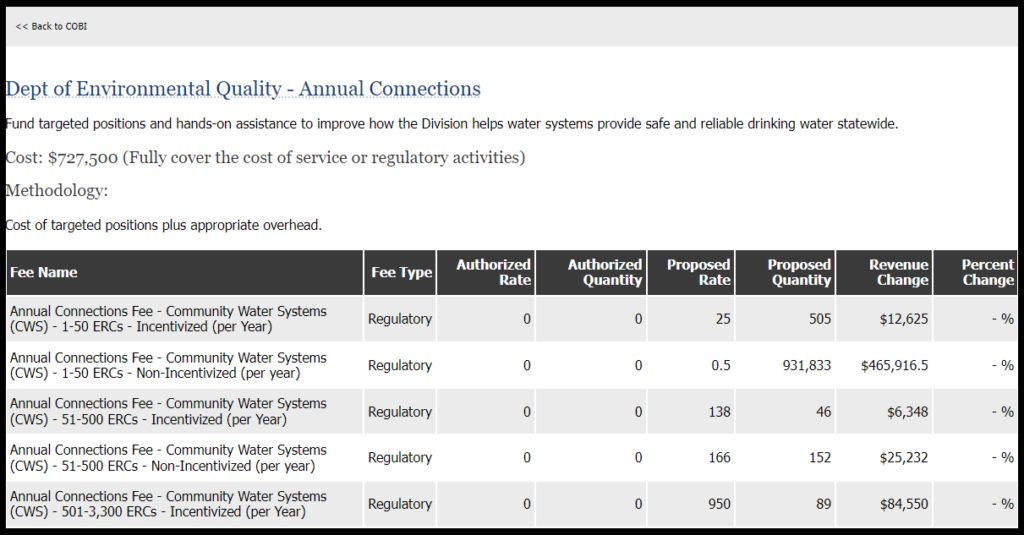

These pieces of legislation, typically the first ten House and Senate bill numbers in each session, officially authorize expenditure of taxpayer resources. These acts include: base budget bills, compensation bills, agencies fees and internal service fund rate bills, supplemental appropriations, and the "bill of bills".

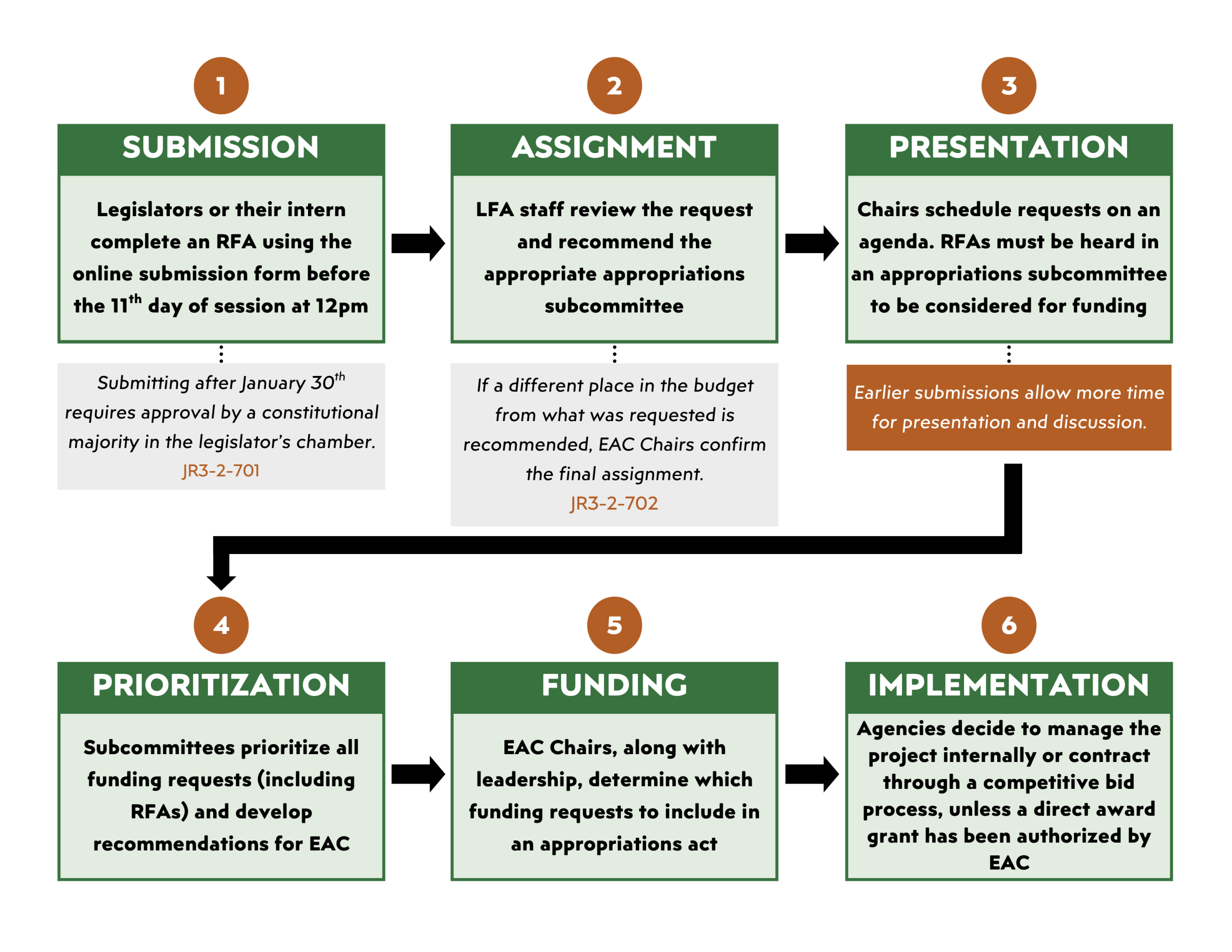

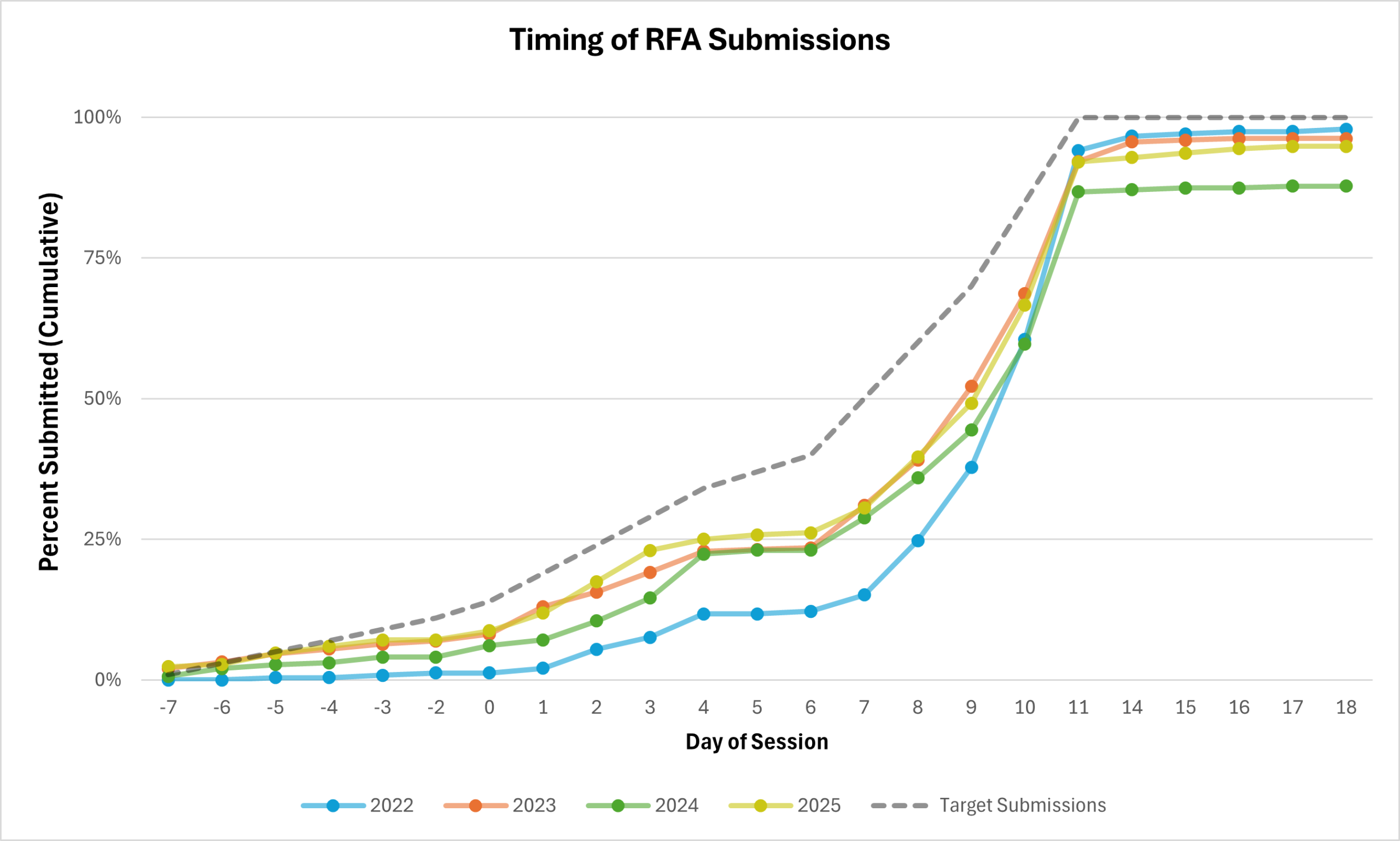

Requests for Appropriations by Legislator

A legislator wishing to obtain funding for a project, program, or entity, without enacting an associated statutory change, may file a request for appropriation with the Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst. Each request is reviewed by the LFA and considered by a subcommittee during the annual general session. This report shows Requests for Appropriation (or RFAs) summarized according to the legislator who requested the funding.

Interactive Budget Visualization

This interactive tool shows Utah's budget by line item. It contains budget data for multiple sessions in a visually consumable format and offers keyword searches.

Budget Slideshow

This file provides a high-level summary of the latest state budget, ideal for Legislator adaptation and use at town hall meetings, conferences, or other speaking engagements.

Fund Balances

The Legislature creates restricted accounts within its major funds for various statewide purposes. Agencies also request authorization to retain unspent amounts, carrying a balance between fiscal years. The reports below detail the yearend balances for restricted accounts within state funds as well as nonlapsing amounts in operating and capital line items.

Budgetingsubcommittees

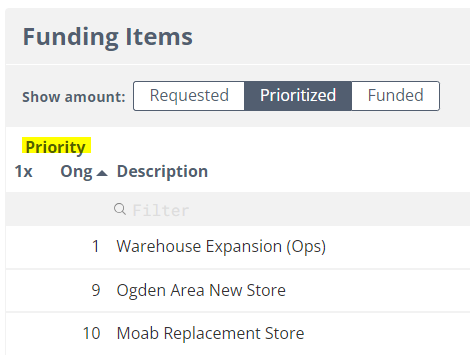

Budget Priority Lists

These documents rank order budget changes according to the affirmed priorities of an appropriations subcommittee. The Executive Appropriations Committee and various caucuses use the lists to compile a unified balanced budget. (JR3-2-402)

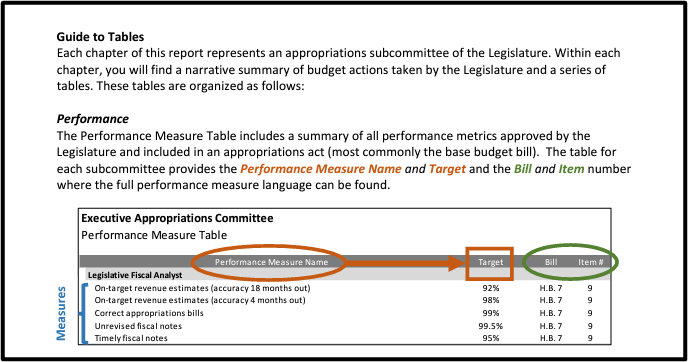

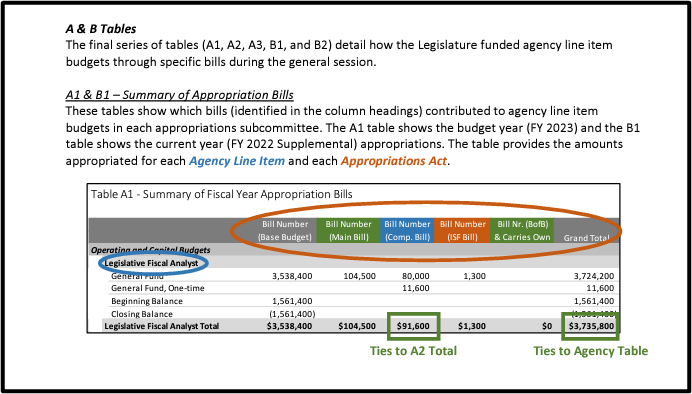

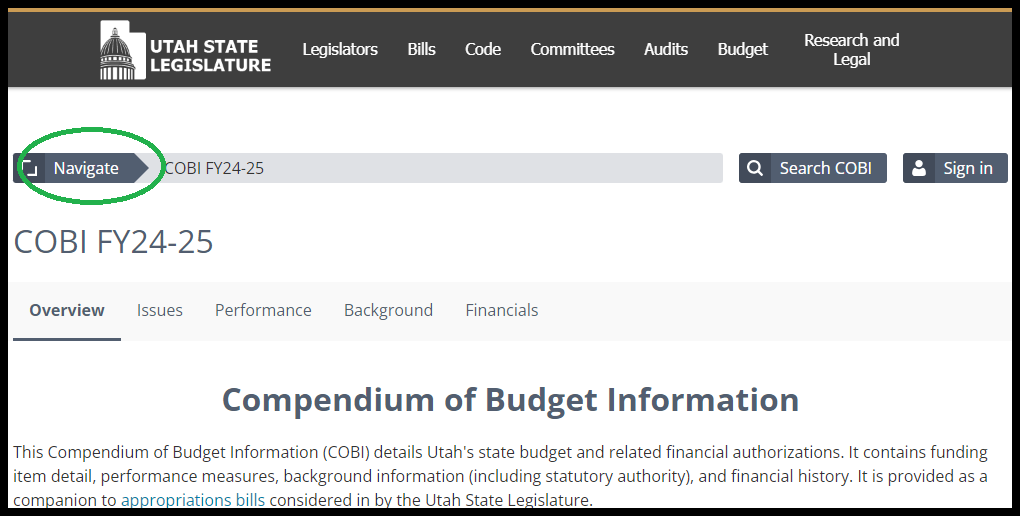

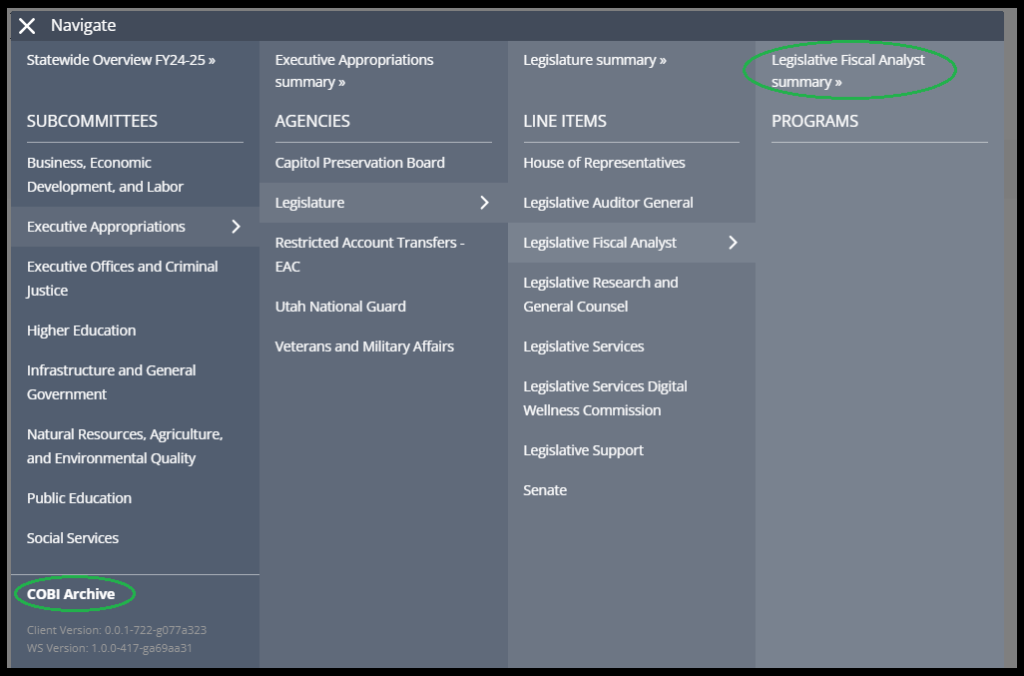

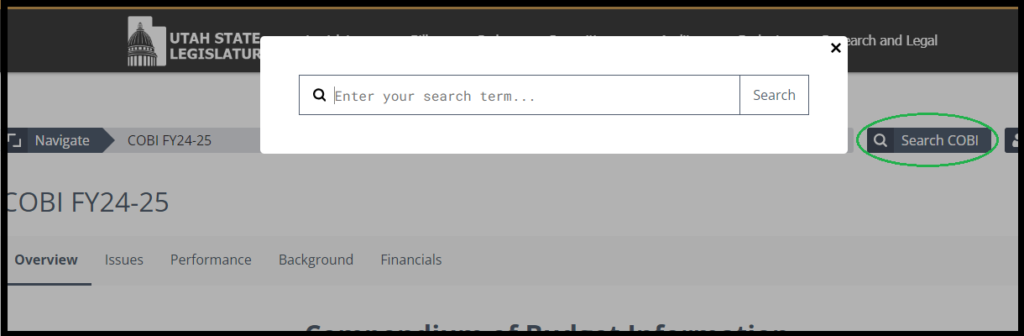

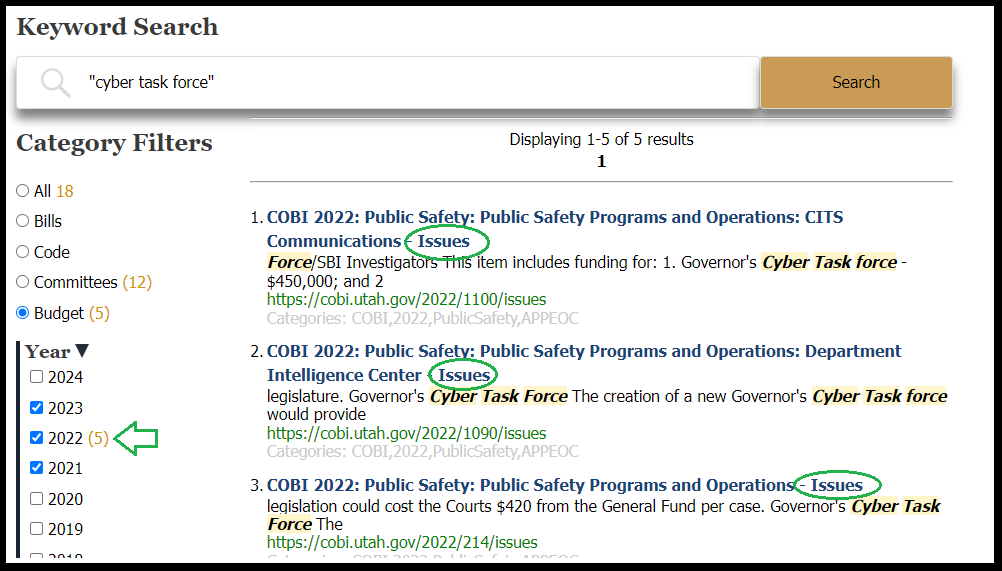

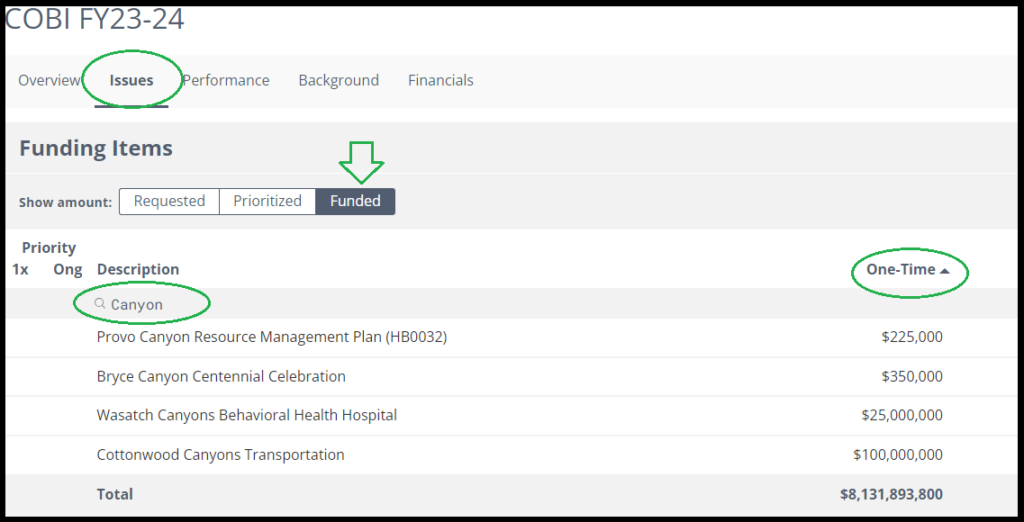

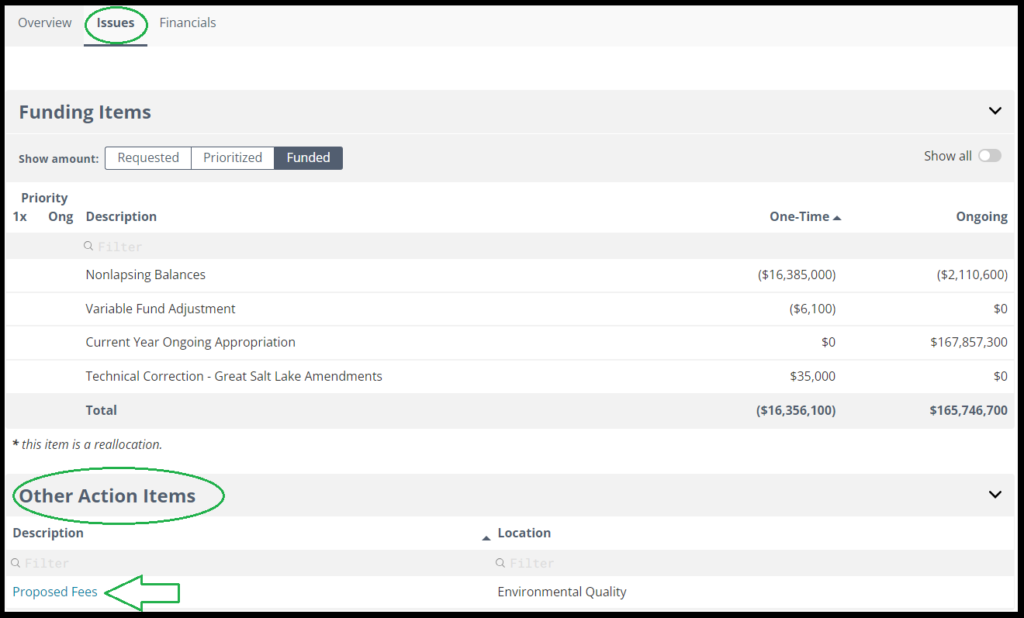

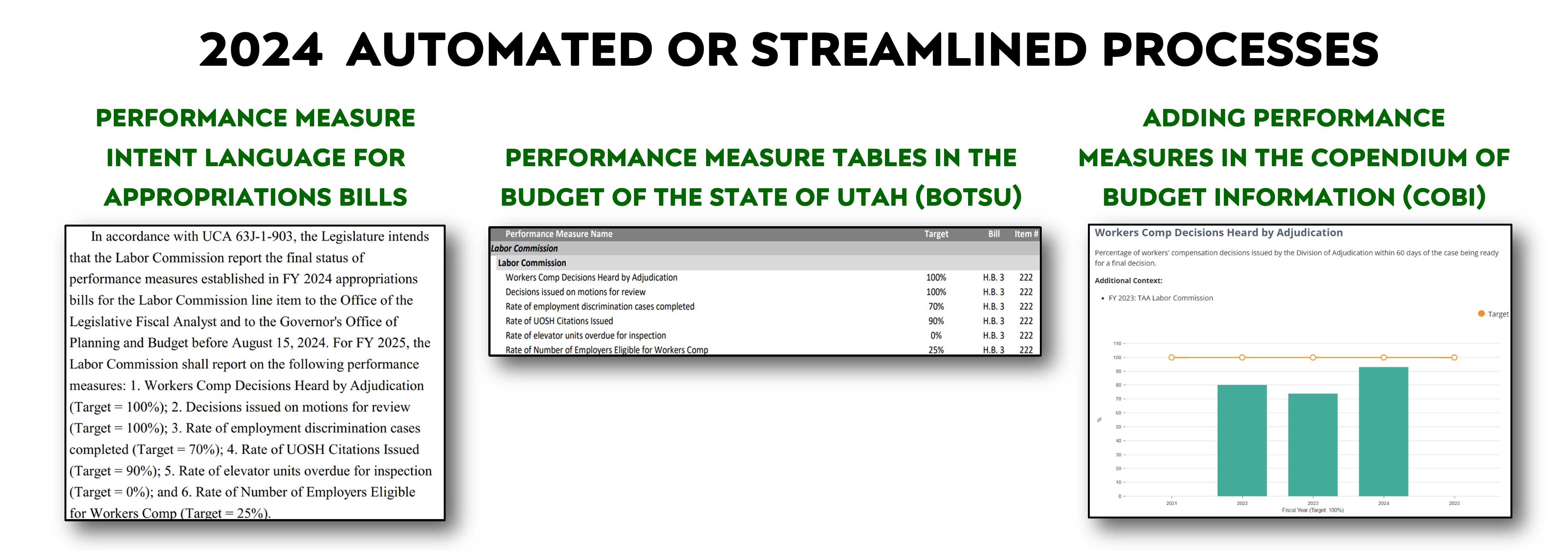

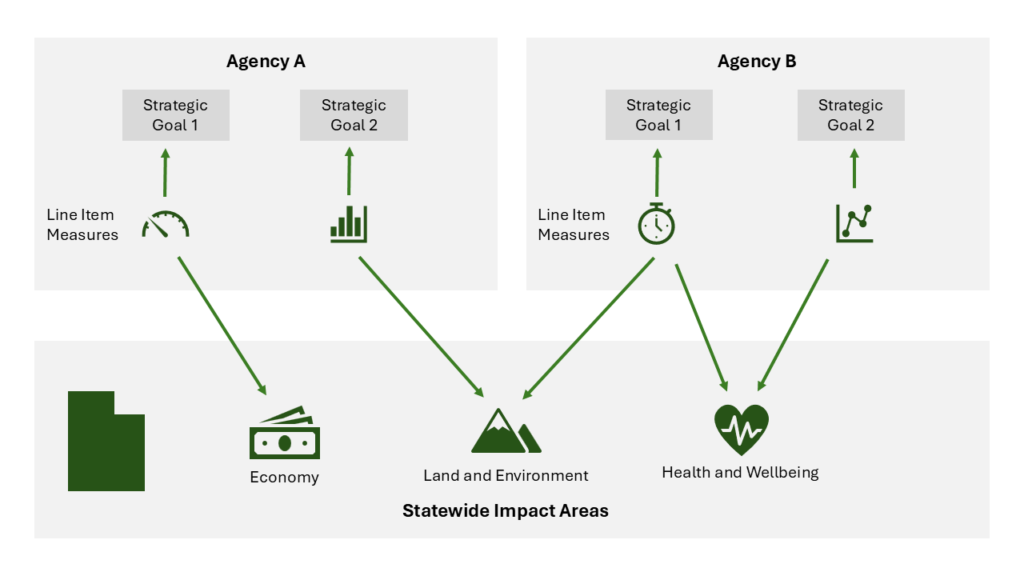

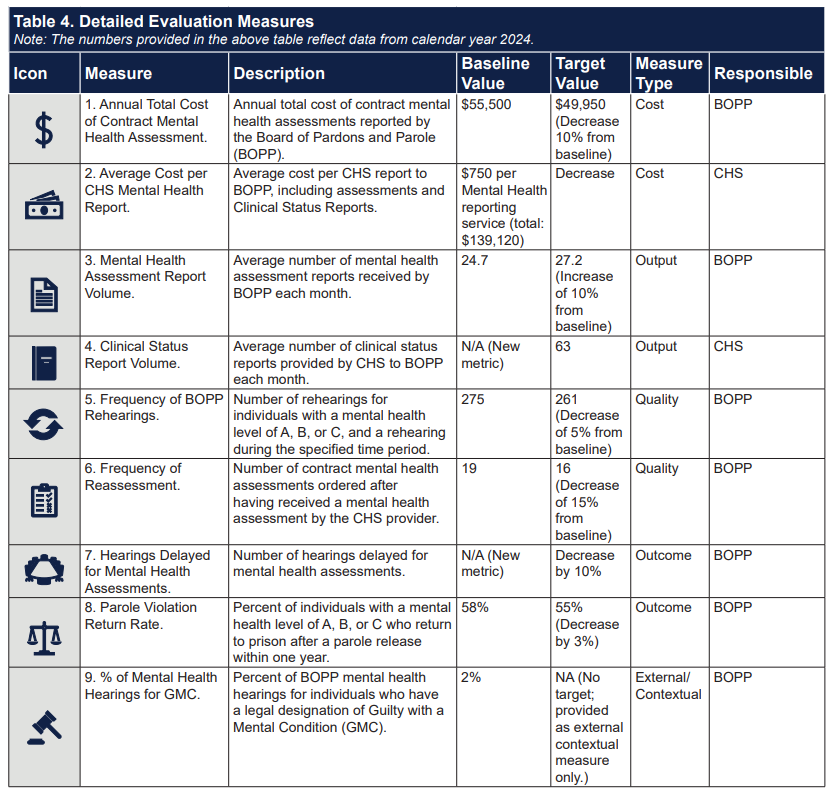

Compendium of Budget Information (COBI)

This online resource details Utah's budget and related financial authorizations. It contains summaries of issues faced by legislators, performance measures, background information (including references to statutory authority), and financial history. It is provided as a companion to appropriations bills considered by the Utah State Legislature.

Appropriations Committees

These links direct to all meetings and actions of the Executive Appropriations Committee and topical appropriations subcommittees. Meeting materials include agendas, minutes, audio/video recordings, reports, and presentations.

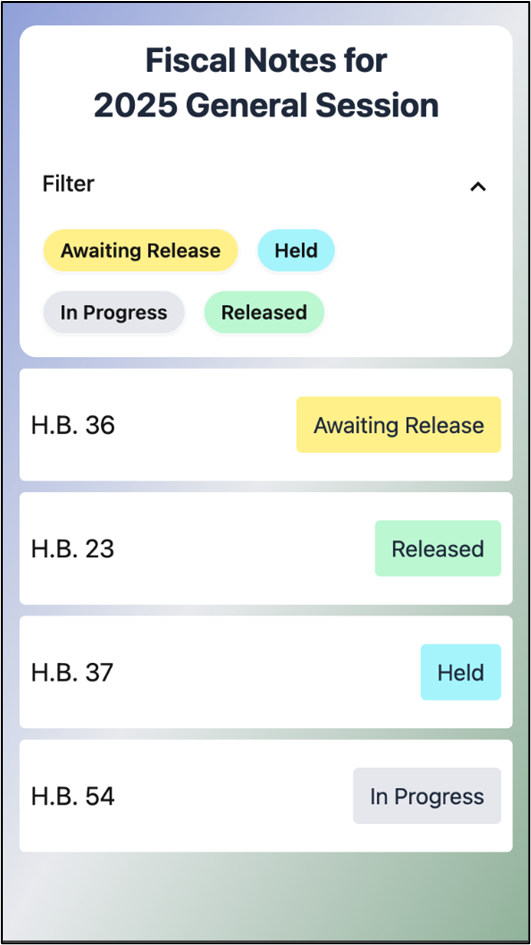

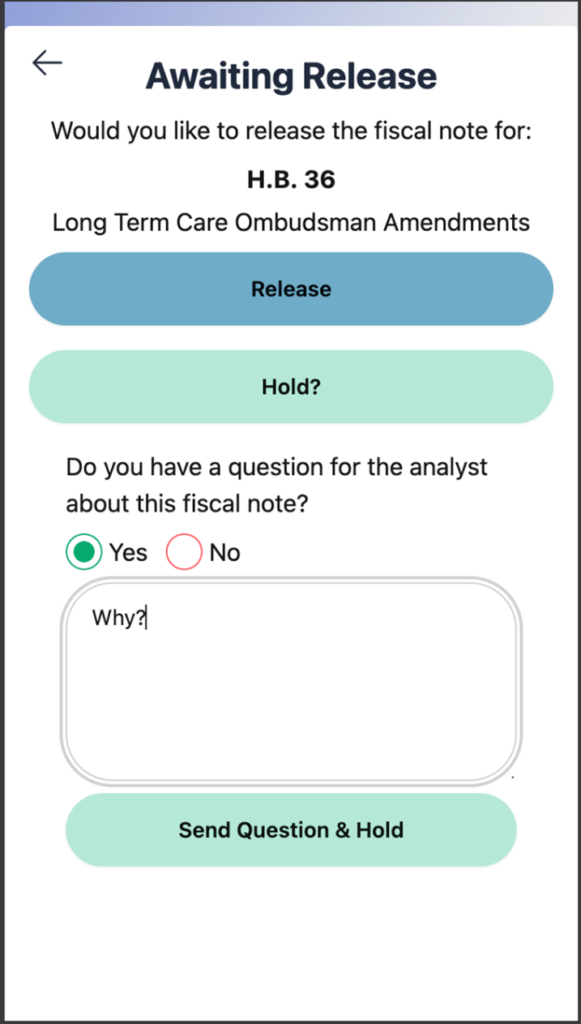

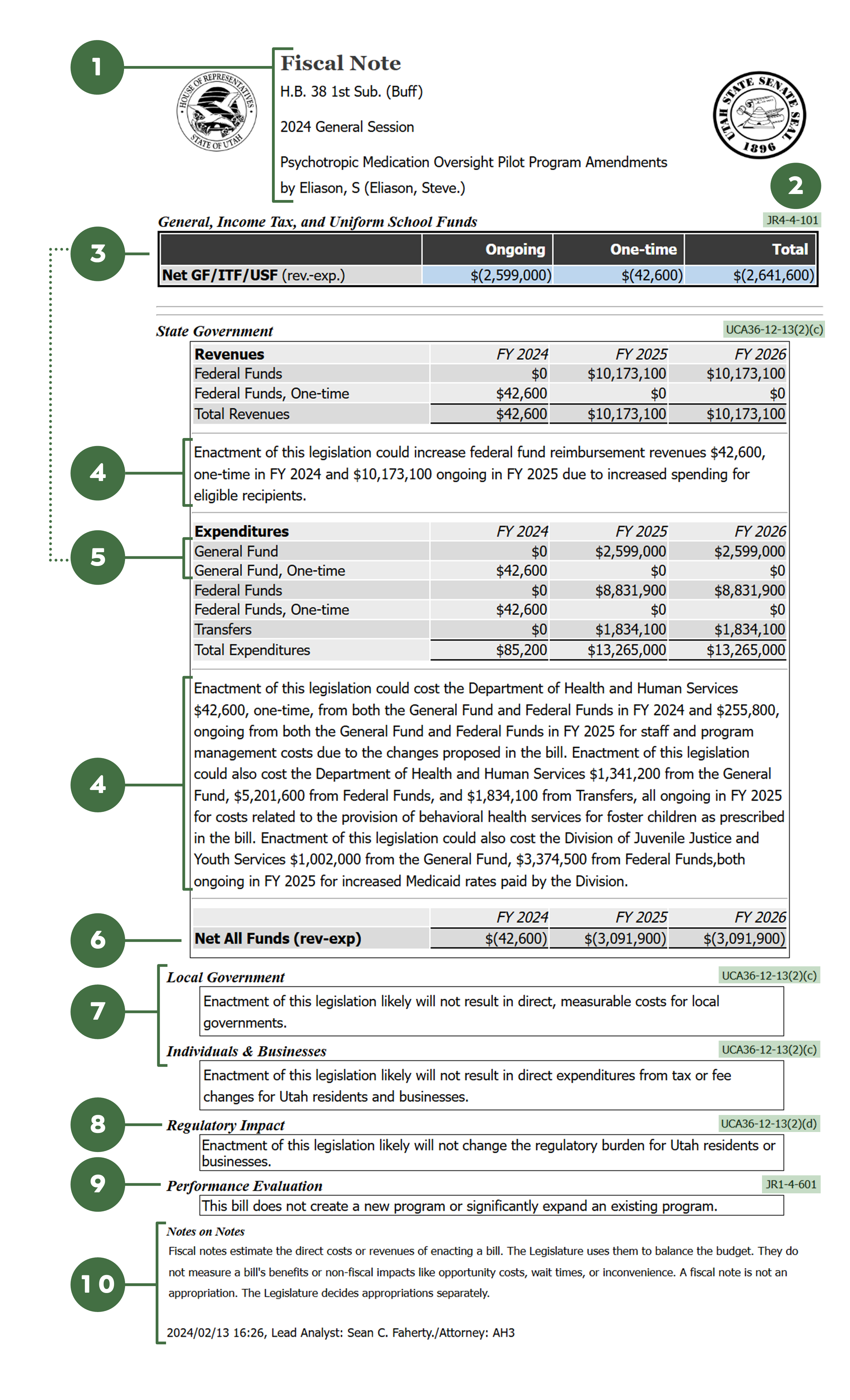

Fiscal Notes and Regulatory Impact Analyses

A fiscal note estimates the direct and measurable costs, savings, revenue gains, or revenue losses associated with implementing a piece of legislation. Fiscal notes are required for every piece of legislation and show impacts for state agencies, local governments, individuals, and businesses. A fiscal note is not a price tag, a cost/benefit analysis, or a funding trigger. Fiscal Notes are not intended to influence the passage of a bill. Regulatory Impact analyses are included on fiscal notes and indicate whether a proposed bill will change regulatory burden for Utah residents and businesses, and if so, whether a bill increases or decreases the burden and whether the change in burden is high, medium, or low.

Standard fiscal notes estimate three years of impact and assume no behavior change. Dynamic fiscal notes project for more than three years and provide four hypothetical scenarios for what might happen in the economy if individuals and businesses change their behavior as the result of a bill. Dynamic fiscal notes are done by legislator request only.

Prior to each General Session, the Legislative Fiscal Analyst trains stakeholders who provide input for Fiscal Notes and regulatory impact analyses. The training covers requirements for each type of note, information on the latest changes to those requirements, and a thorough review of the interactive software program used to submit input. (UCA 36-12-13(2); JR4-2-403)

Economylongtermfiscalhealth

Revenue Volatility Report

This triennial report measures the experienced variability of state tax and fee collections, as required under UCA 36-12-13(2)(e). Policymakers may use the magnitude of that variability to determine appropriate reserve ratios.

Long Term Budget

This triennial report required under UCA 36-12-13(2)(e) looks at a five-year window for revenues and expenditures, accounting for known policy changes for programs appropriated from major funds and tax types.

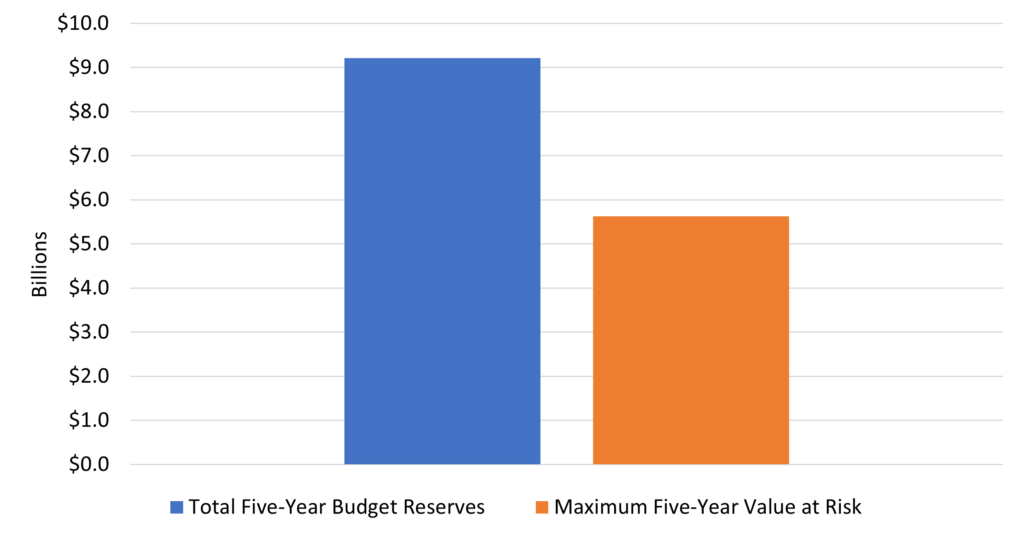

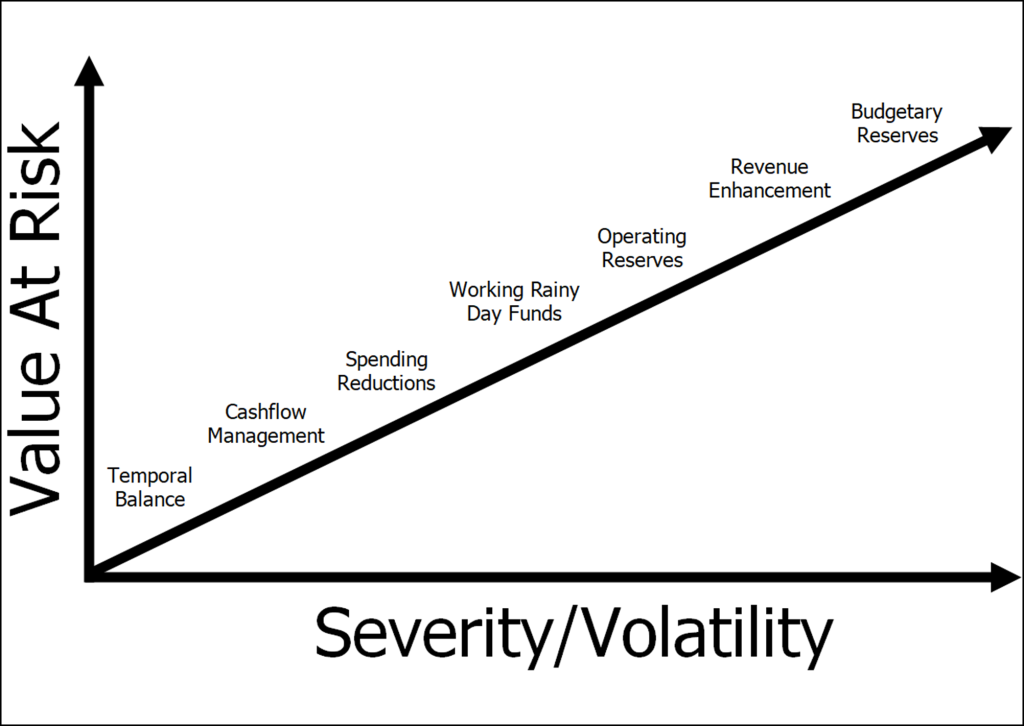

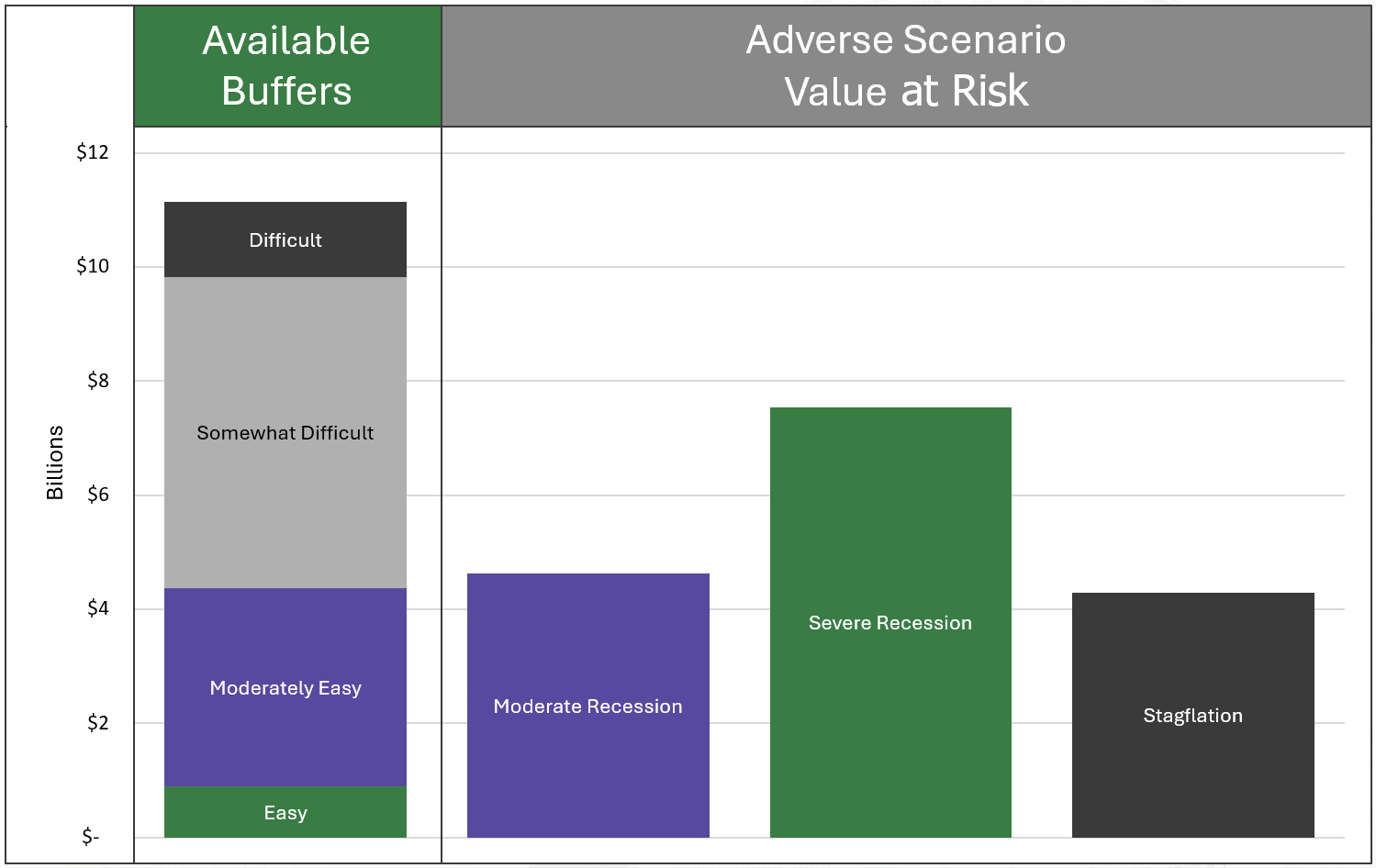

Stress Testing

These simulations provide insight into the impact an economic downturn might have on state revenue and expenditures, which can then provide information to legislators, and others, about how much the state should set aside in reserves to endure a downturn. These analyses are required every three years under UCA 36-12-13(2)(e).

Fiscal Health Dashboard

This online resource shows the latest condition of fiscal measures like revenue and spending, but also covers greater measures of financial health like extent of long-term obligations, status of reserves, and performance of economic indicators against assumptions.

Economyrevenueandtaxation

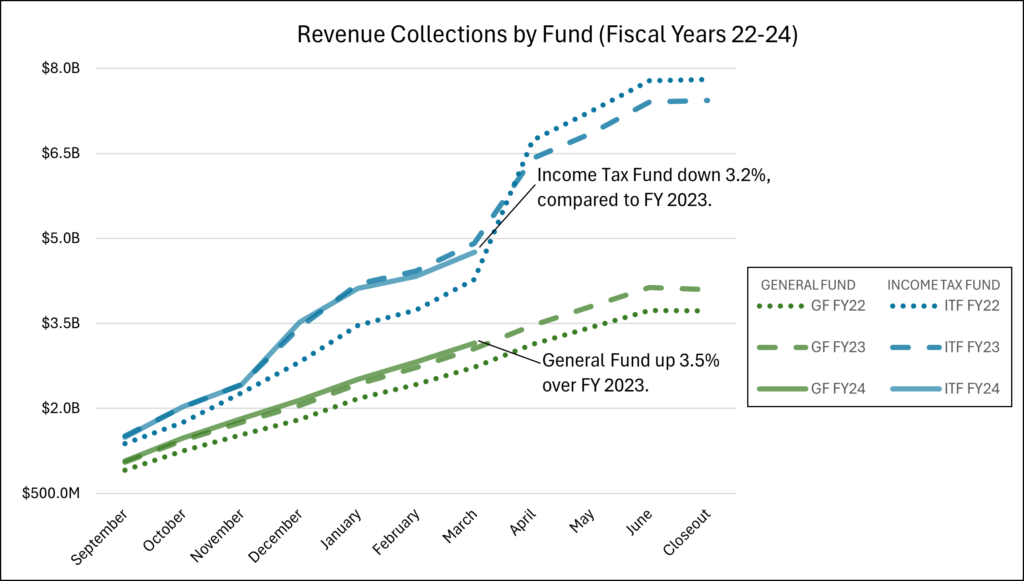

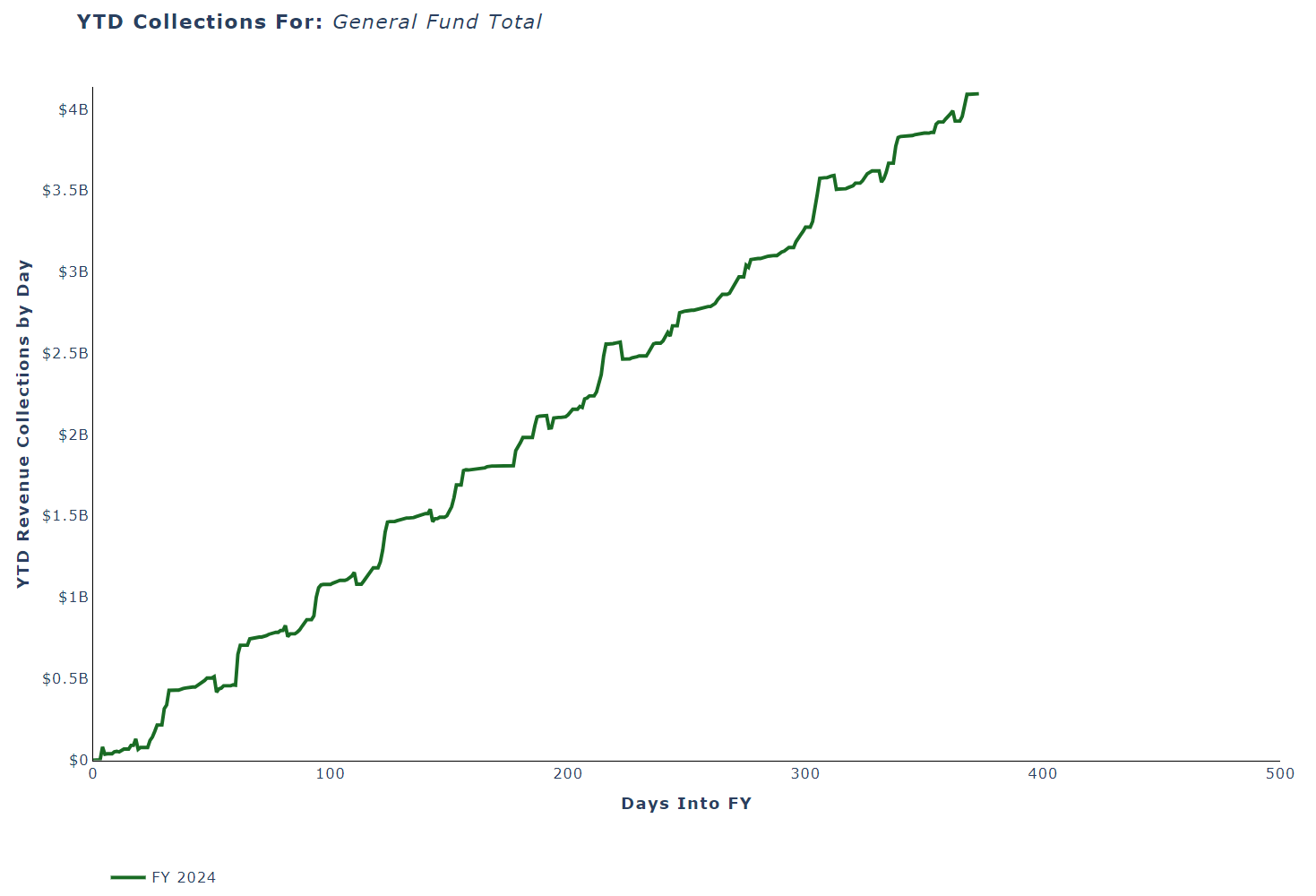

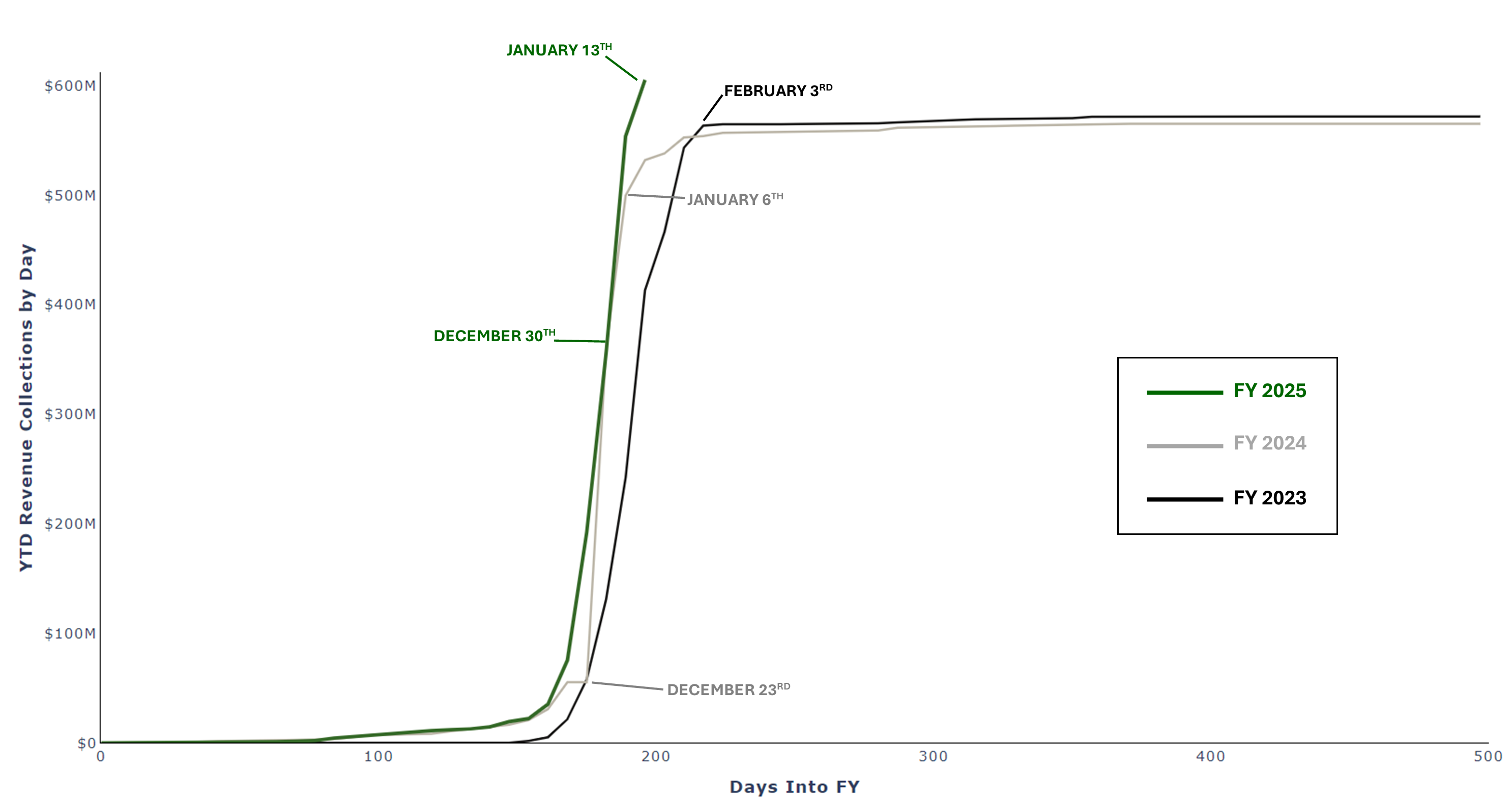

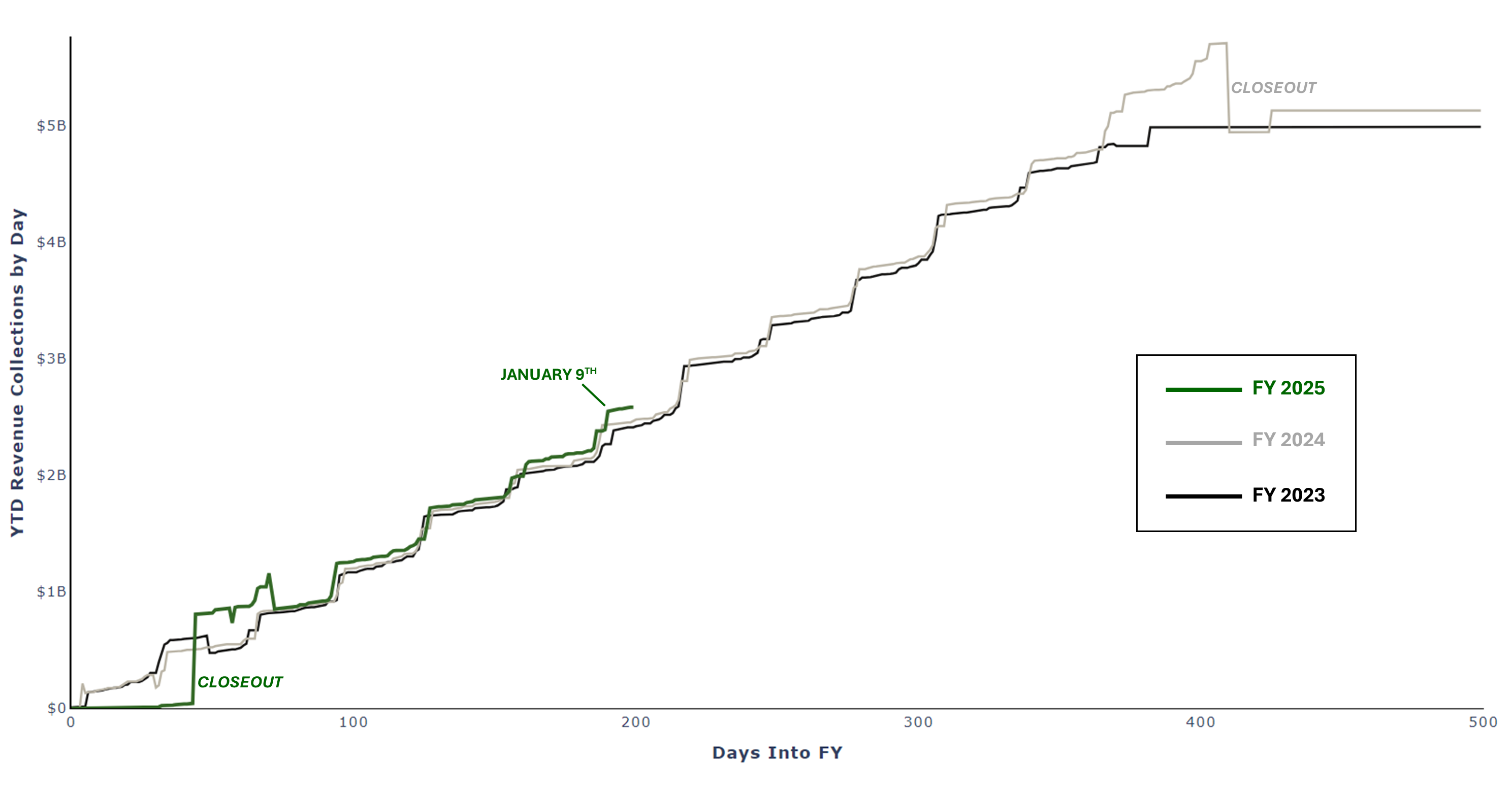

Revenue Collections and Estimates

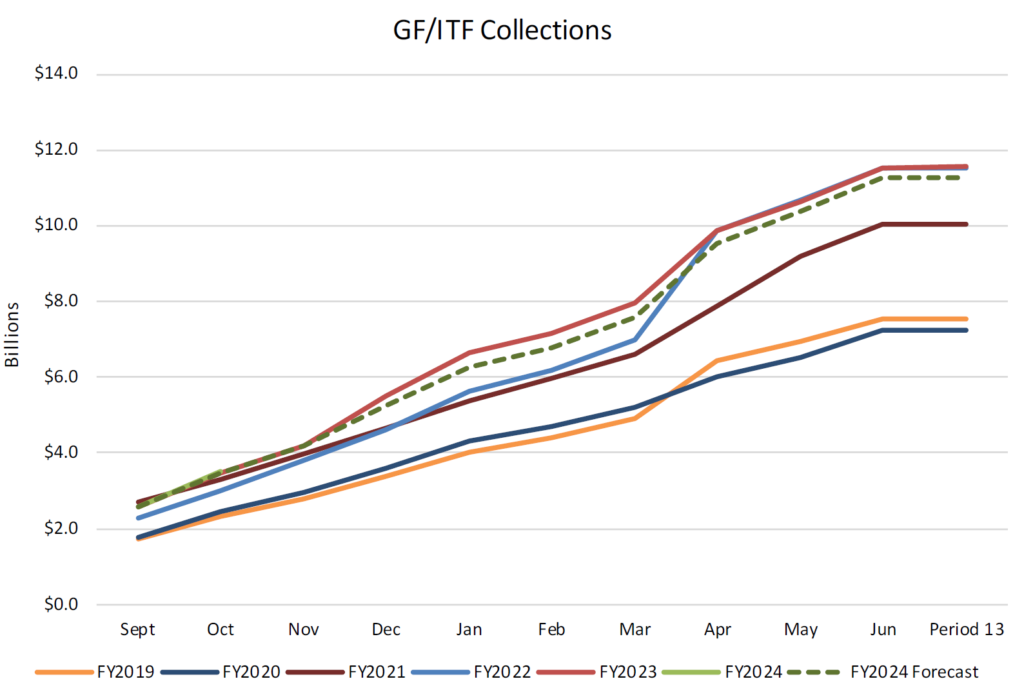

These estimates of future tax collections establish a target for budgeting, as required by UCA 36-12-13(2)(a). Forecasts are developed in consensus with private sector consultants, the Governor's Office of Planning and Budget, and the Utah State Tax Commission. Point forecasts are made in December and February, with ranges updated in June and October. Estimates are also used to draft the monthly Revenue Snapshots. These snapshots provide regular updates on the state's revenue collections, note whether collections are above or below target, and provide the macroeconomic context through which to interpret collections.

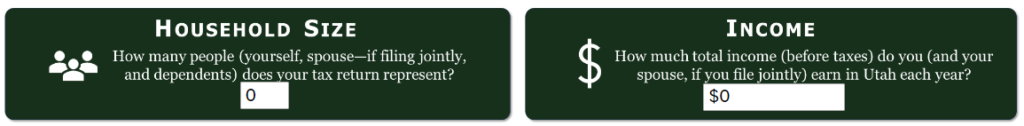

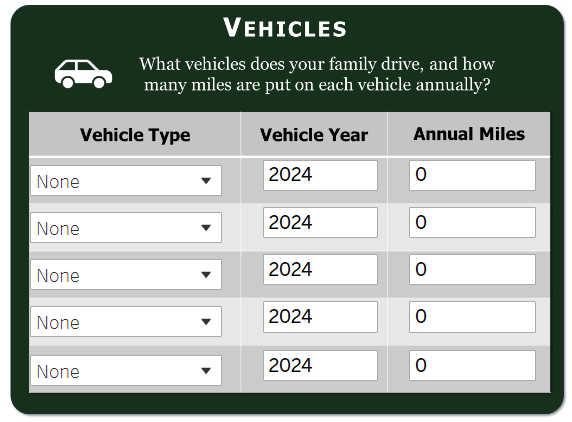

Taxpayer Receipt

This online interactive tool allows a taxpayer to view an estimate of how the taxpayer's tax dollars are spent for state government purposes.

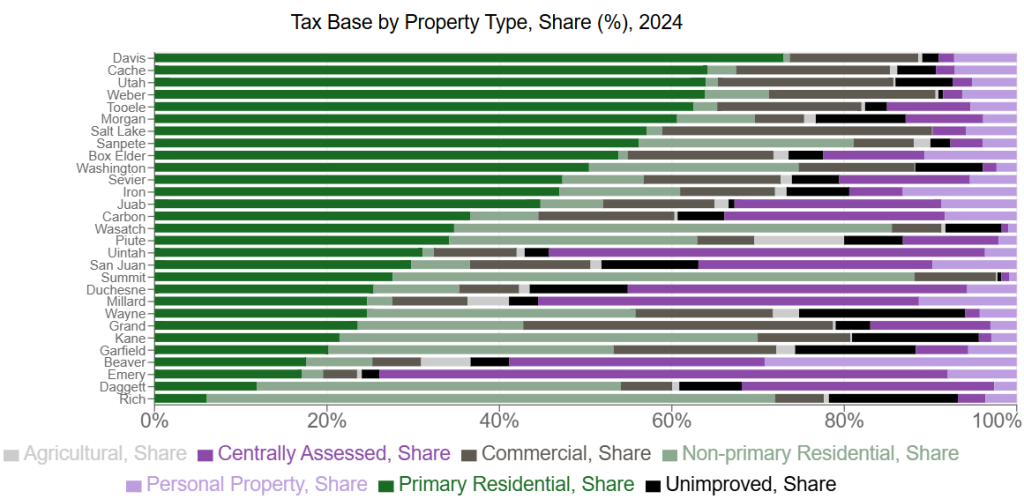

Property Tax Application

Vesta is an interactive web application developed by the Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst and designed to provide insight into the Utah state property tax system. Using data from the Tax Commission, the application allows users to compare taxing entities and property tax types.

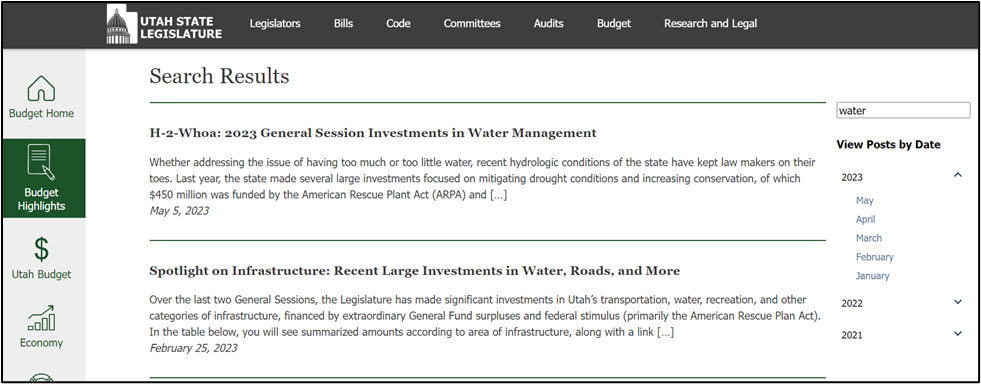

Featured

Long-term Vision: Looking Out at Our Future

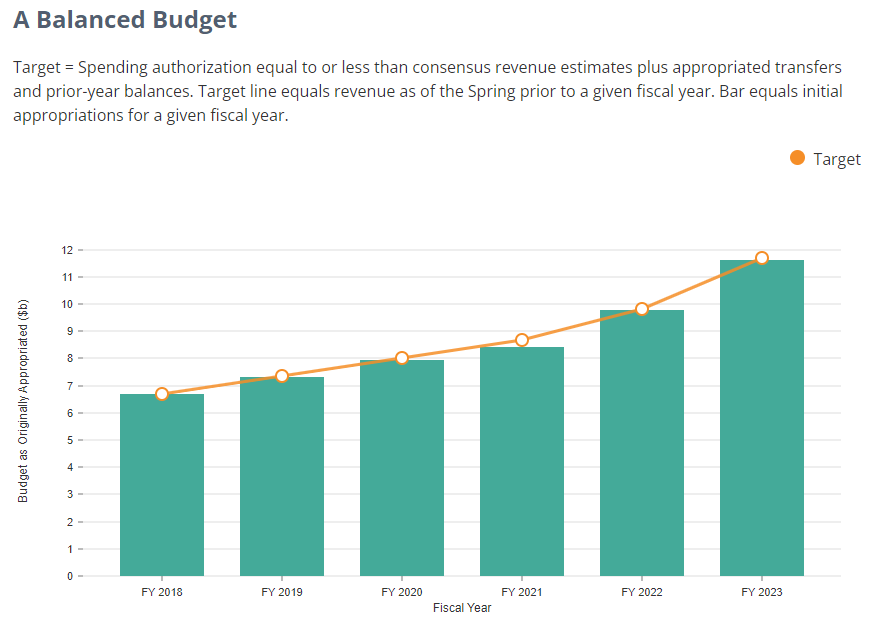

Utah legislators have long known the benefits of forward thinking. After the "Dot-com" bust of the early 2000s, they developed tools like temporal balance and the working rainy-day fund to assure the state could weather the next recession. They were the first in the nation to implement evidence-based rainy-day policy in 2008. In the 2018 General Session, they took yet another step toward improved long-term fiscal health.

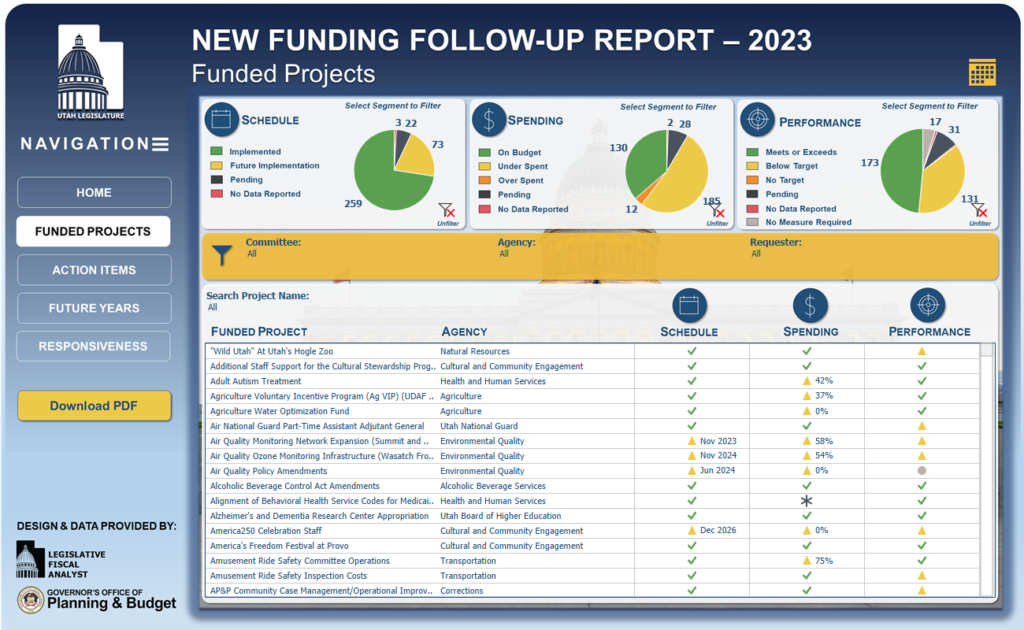

Follow-up Report: Time to Revisit Budgets of the Past

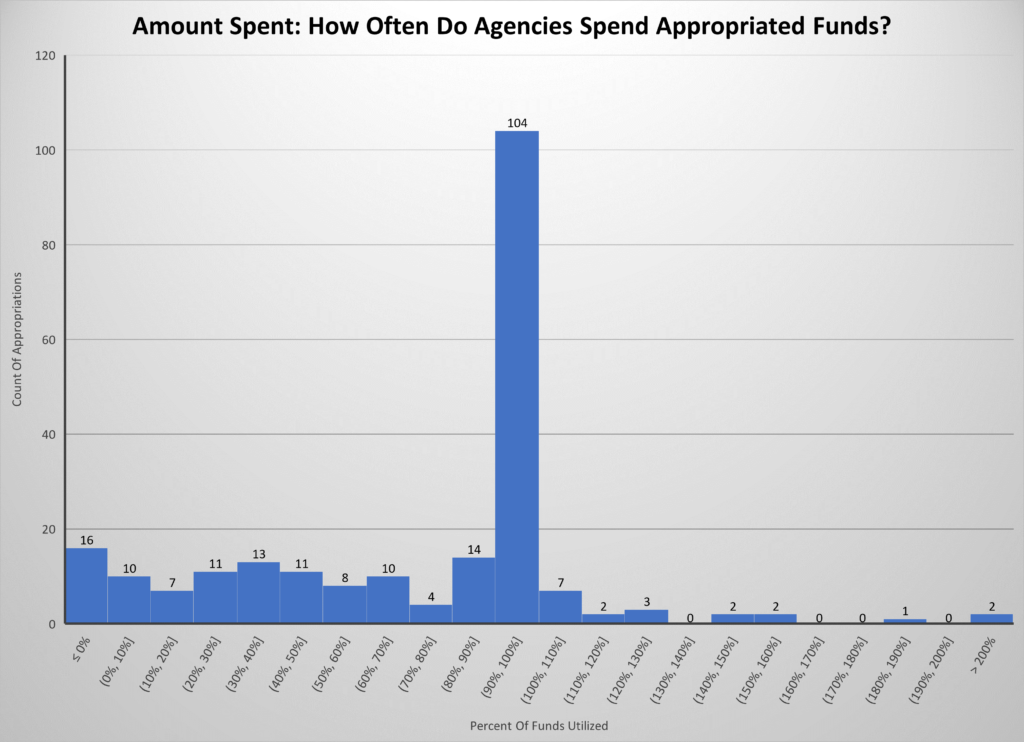

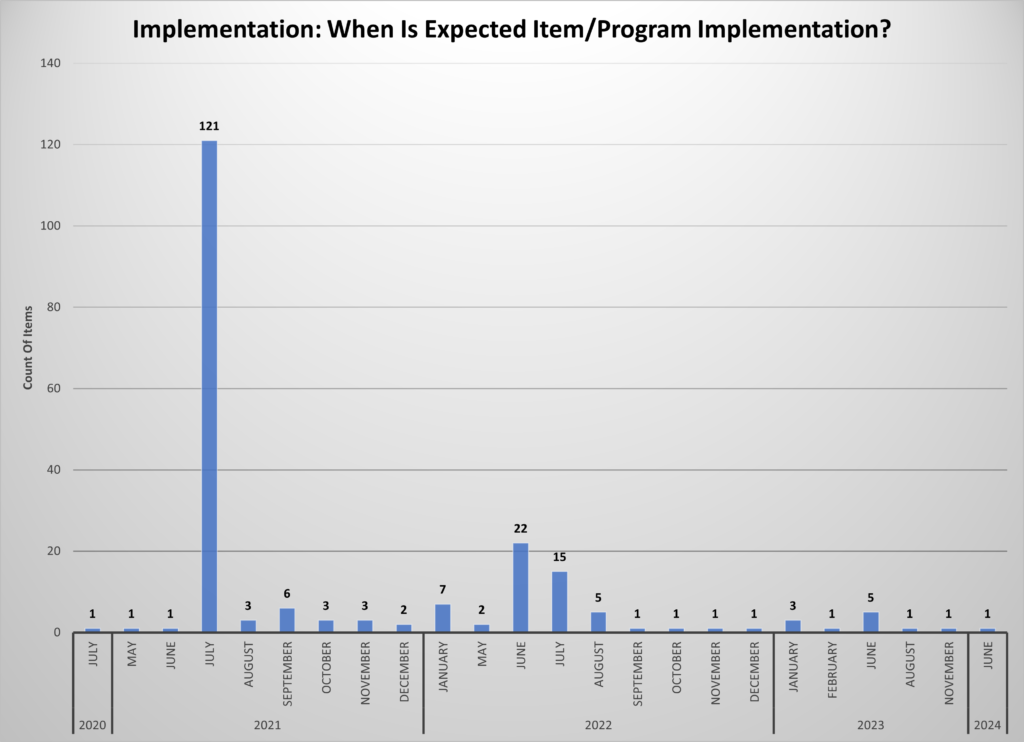

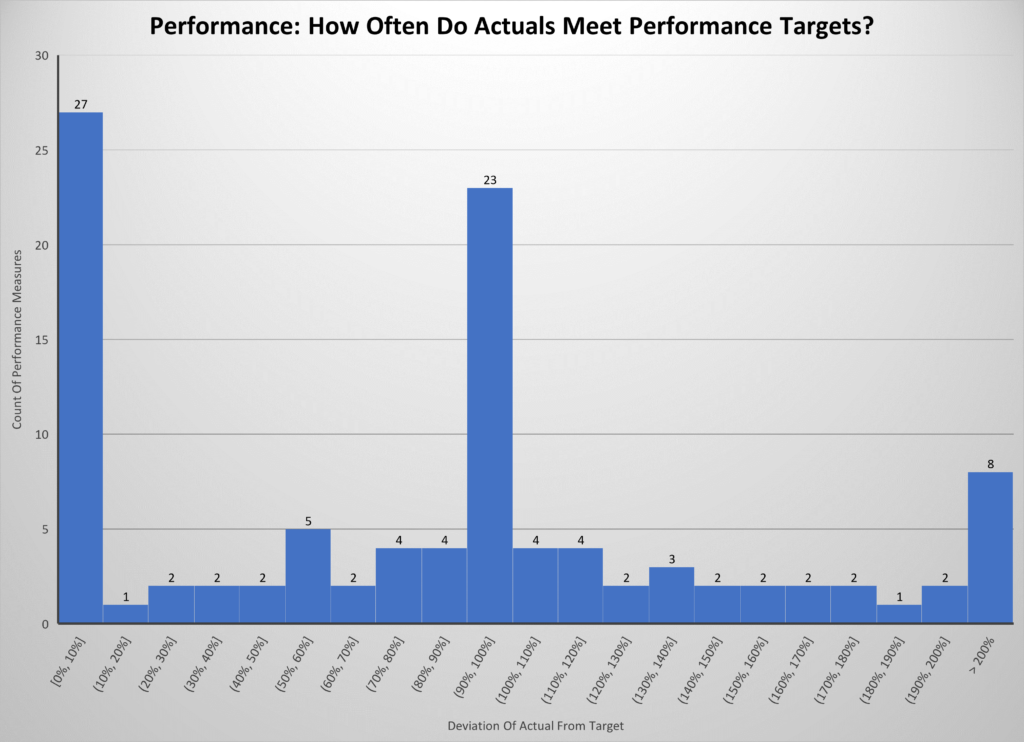

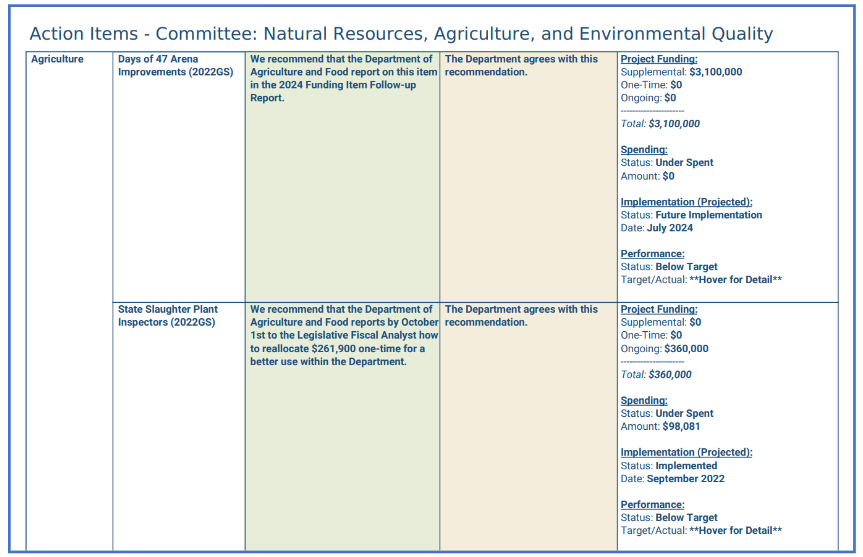

Each summer, the Legislative Fiscal Analyst looks-back at prior year appropriation items and fiscal notes to determine accuracy of budget, schedule, and performance. This year, Clare Tobin Lence presented the Fiscal Note and Budget Item Follow-up Report in Executive Appropriations' July meeting. She and her colleagues highlighted a number of follow-up items in the meeting, but all those of consequence are included in the report itself. This year's review covered 232 budget items and fiscal notes from four past General Sessions. Of those, 84 (36%) were included in the body of the report, indicating that they require consideration by the Legislature. The Executive Appropriations Committee referred the report to appropriations subcommittees for further action. The entire 104 page report can be found here: https://le.utah.gov/interim/2018/pdf/00002986.pdf

A Tally of Utah's $252 Million Revenue Surplus by Source

Fiscal Year 2018 is over. And it ended with a bang. The State closed the fiscal year with a $252 million revenue surplus. Of the $252 million, $210 million stemmed from better-than-expected Education Fund performance and $42 million came from the General Fund.

The Transportation Fund ended FY 2018 in a revenue deficit at -$9 million. This was drive largely gasoline tax (-$4 million) and diesel tax (-$8 million). All other sources to the Transportation Fund ended the year +$3 million above target.Behind the surplus was stronger than expected income tax revenue (+$108 million), corporate tax revenue (+$100 million), sales tax ($+29 million), and other General Fund revenue (+$13 million). Click on these interactive graphics to further explore components of the revenue surplus.

A portion of the revenue surplus will be deposited into reserve funds and other accounts. Those deposits, combined with performance on the spending side, will determine the State's final budget surplus and amount of revenue available to policymakers in the 2019 General Session.Legislative Staff Offices Receive Valued Recognition

Utah's legislative staff offices are honored to receive the 2018 Ethical Leadership Award for Government from the Daniels Fund and Daniels Fund Ethics Initiative at the University of Utah's Eccles School of Business. Each year the award goes to businesses, nonprofits and government agencies that demonstrate the highest ethical standards and practices in the state of Utah. The award is especially meaningful not only because it recognizes what we strive for each and every day, but also because the staff offices received it jointly.

Read more about the Daniels Fund Ethics Initiative here:

https://danielsfundethicsinitiative.business.utah.edu/community/utah-ethical-leadership-awards/

Read more about the Daniels Fund Ethics Initiative here:

https://danielsfundethicsinitiative.business.utah.edu/community/utah-ethical-leadership-awards/

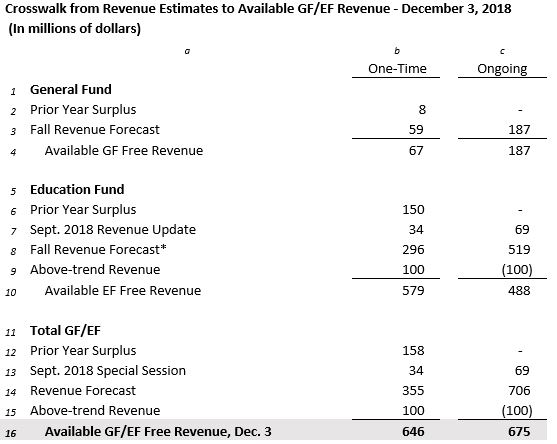

State Closes Fiscal 2018 with $158 Million Budget Surplus

On October 16, the Legislative Fiscal Analyst’s Office reported to members of the Executive Appropriations Committee that Utah closed fiscal year 2018 with a budget surplus of nearly $158 million ($8 m GF/$150 m EF). For purposes of comparison, at the same time the prior year, fiscal year 2017 ended with a $27 million surplus. This is certainly good news in that it means Utah’s economy expanded beyond expectations in FY 2018. At the same time, the size of this surplus suggests that it is not sustainable in the long-run. Using this one-time money wisely will avoid making promises that cannot be kept.

To that end, Utah also made significant deposits into reserve accounts at the end of FY 2018. An additional $6 million went into the general rainy-day fund, $65 million into the education rainy day-fund, and $30 million into the Medicaid rainy-day fund. The State deposited $1 million into the Disaster Recovery Account and $4 million into the Wildland Fire Suppression fund. These amounts are on top of the $95 million that legislators appropriated to reserves last General Session ($73 m General RDF/$12 m Education RDF/$10 m Student Growth Account).

You can find further information on the surplus and reserve fund balances on the Division of Finance's Financial Highlights document and on the Legislature's Fiscal Health Dashboard. These numbers are preliminary and subject to change as the state completes its annual audit of financial statements.

You can find further information on the surplus and reserve fund balances on the Division of Finance's Financial Highlights document and on the Legislature's Fiscal Health Dashboard. These numbers are preliminary and subject to change as the state completes its annual audit of financial statements.

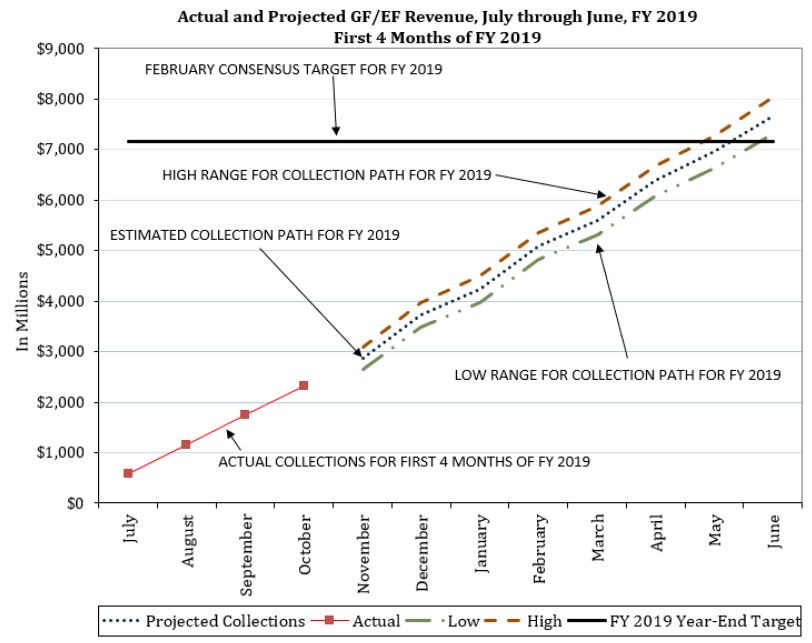

Fourth Month Revenue Slows Down a Bit, Still Strong

The Utah State Tax Commission released its TC-23 revenue report for the first four months of FY 2019 today. The report, as interpreted on our monthly revenue snapshot, shows that growth slowed from the third to the fourth month, from 13.8% to 11.2%. The current growth rate puts our estimated collections range above the projected totals for the year. Combined General and Education Fund revenue grew by 11.2% in the first four months, compared with expected growth of 5.7%. If one adjusts the starting point for Utah's $252 million FY 2018 revenue surplus, tax collections would need grow by only 1.9% for the year in order to meet expectations.

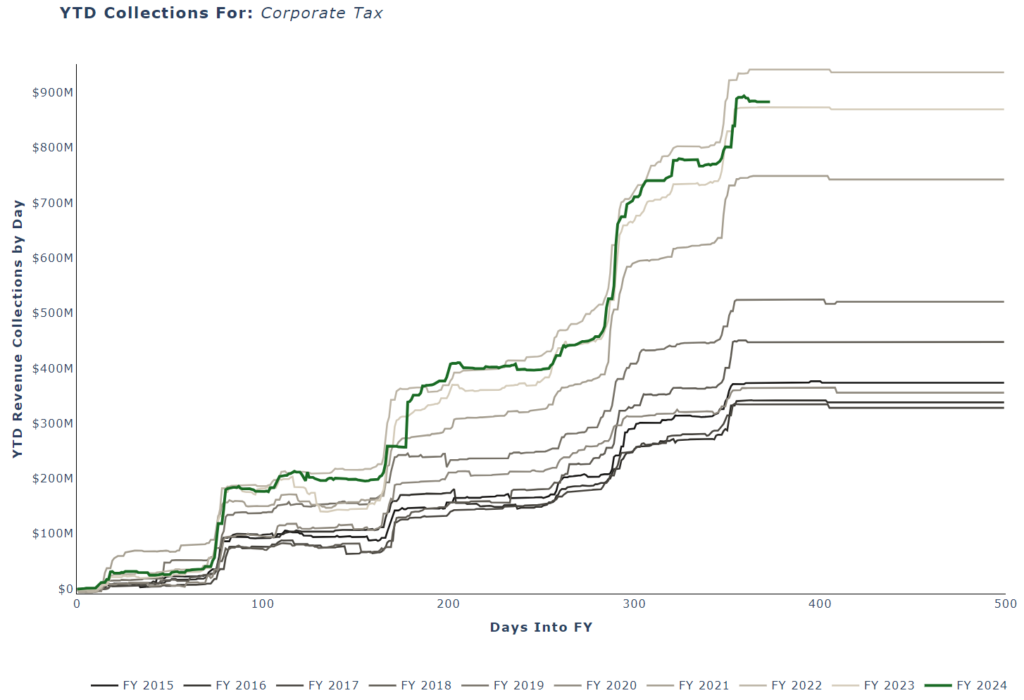

Growth to date is most pronounced in the Education Fund, where first quarter collections approached an 12.9% year-over-year growth rate. Much of this came in corporate income taxes. We believe much of that growth is associated with federal tax reform. Such a growth rate is not sustainable in the long-term.

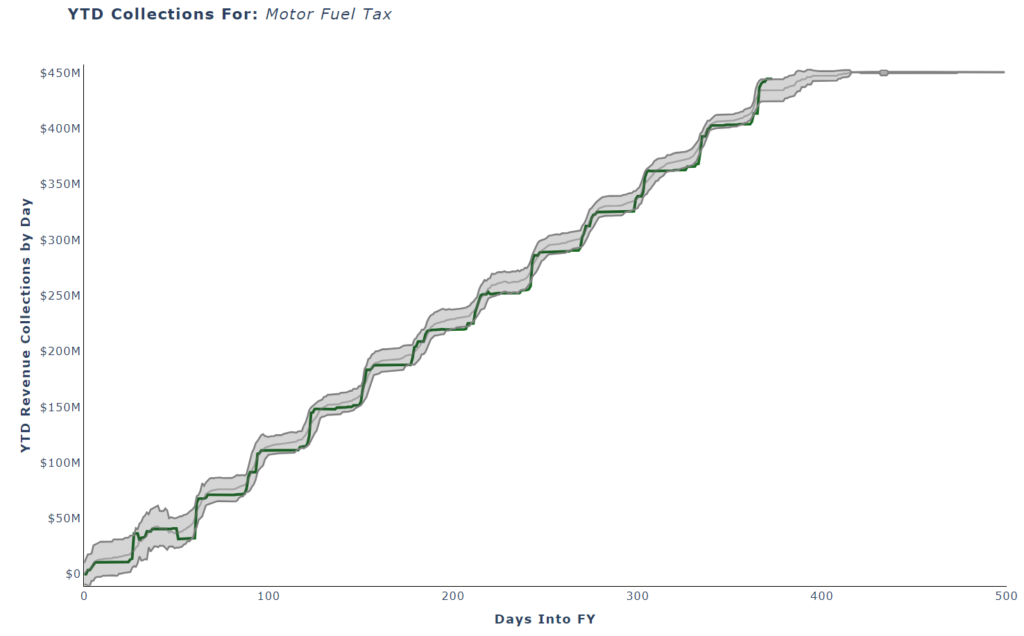

Gas and other fuel taxes met expectations at $202 million through the first four quarters.

For more, read our monthly revenue snapshot, here.

Growth to date is most pronounced in the Education Fund, where first quarter collections approached an 12.9% year-over-year growth rate. Much of this came in corporate income taxes. We believe much of that growth is associated with federal tax reform. Such a growth rate is not sustainable in the long-term.

Gas and other fuel taxes met expectations at $202 million through the first four quarters.

For more, read our monthly revenue snapshot, here.

State Revenue Remains Strong but Caution Encouraged

The Executive Appropriations Committee adopted revised revenue estimates for FY 2019 and new estimates for FY 2020. When combined with the year-end surplus from FY 2018 and after adjusting for above trend revenue, available revenue is expected to be $646 million one-time and $675 million ongoing. Details on available revenue can be found online.

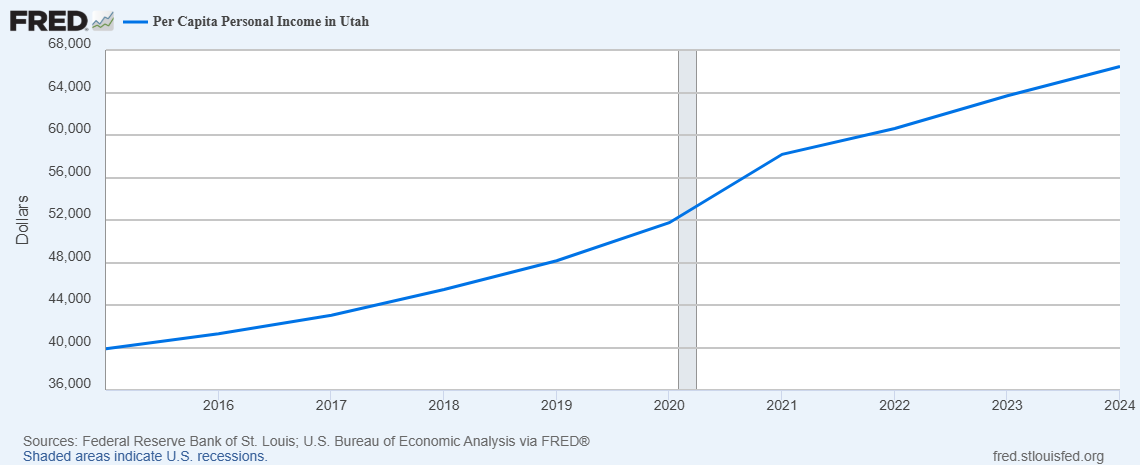

Economic Indicators remain strong. Both General Fund and Education Fund exhibit strong growth largely due to income tax and retail sales tax collections. The current growth rates for Education Fund at 12.9% and General Fund at 7.1% are not historically sustainable. Wage growth is currently estimated at 5.6% and taxable sales are estimated at 6.0% growth and as the largest contributors to the funds above are well below current collections.

As a state, the last time we saw collection rates this high was during the 2006-2007 business cycle. If the current expansion lasts another six months we will be in the longest expansion in the modern era. Let's not forget, all good things come to an end.

Economic Indicators remain strong. Both General Fund and Education Fund exhibit strong growth largely due to income tax and retail sales tax collections. The current growth rates for Education Fund at 12.9% and General Fund at 7.1% are not historically sustainable. Wage growth is currently estimated at 5.6% and taxable sales are estimated at 6.0% growth and as the largest contributors to the funds above are well below current collections.

As a state, the last time we saw collection rates this high was during the 2006-2007 business cycle. If the current expansion lasts another six months we will be in the longest expansion in the modern era. Let's not forget, all good things come to an end.

Revenue Growth Slows a Bit Through Five Months

Every month the Tax Commission releases a monthly revenue snapshot. This gives us a chance to compare what’s actually happening this the projected figures. This past month’s report showed revenue growth slowing slightly to 11.1%. In October revenue growth was 13.8%. In November it was 11.2%.

Overall, revenue is moving closer towards the current target of 7.4%. Behind the continued strong growth is strong withholding (9.1%), sales tax (6.7%), and corporate tax (143.7%). Federal tax reform is partially responsible for the strong corporate receipts.

For more, read our monthly revenue snapshot, here.

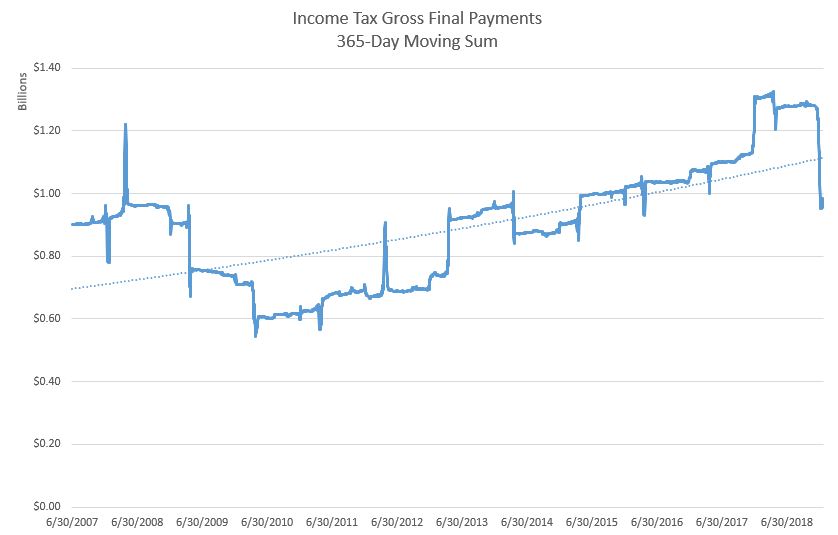

A Sharp Drop in Gross Paids Headlines the Revenue Picture through 6 Months of 2019

The Tax Commission released their 6th month TC-23 on January 22nd. We are halfway through the fiscal year. Through the first 6 months, the state has collected about 45% of the current revenue collection forecast. Typically, at this point in the year, the state would have collected between 46% and 51% to reach target.

The biggest surprise was the abnormally large difference between last year’s income tax payments and this year’s payments. With income tax withholding (10.7%) and corporate tax (64%) above target, and sales tax collections on target (5.9%), the big question is whether April’s income tax payments will be abnormally large because of federal tax reform.

Source: LFA analysis of the 365-day moving average of income tax gross final payments

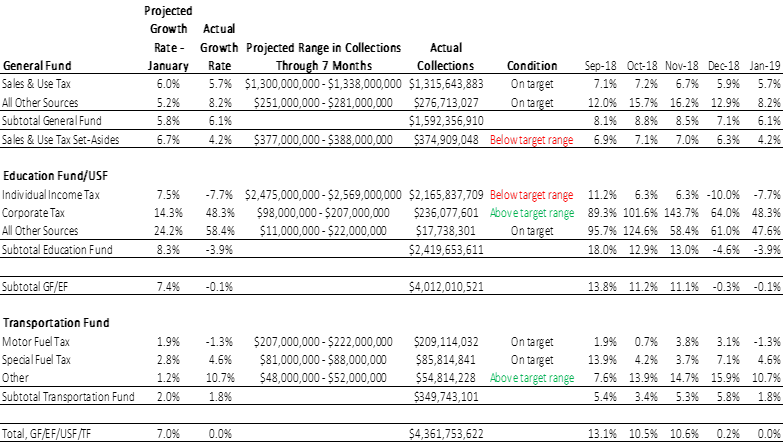

Overall, General Fund and Education Fund collections reached $3.4 billion through the first 6 months, representing a year-over-year decline of 0.3%. The target is $7.6 billion. A snapshot of the collections is in Figure 2. The figure also reports on the top right where revenue growth has been over the past 4 months.

Source: TC-23 Revenue Snapshot

More details of the revenue picture through 6 months is available here.

Income Tax Revenue Below Target Range

The Tax Commission’s TC-23 was released earlier today. The report, which captures a snapshot of revenue collections through the first 7 months of fiscal year 2019, shows that revenues from most sources are on target or above target.

That’s not the case, though, for the largest revenue source – income tax. Income tax is down 7.7% year-to-date. What’s causing this? Gross final payments and refunds.

Although income tax withholding, the largest component source of income tax revenue, is strong at 8.2% year-over-year, individuals filing earlier than the April 15th deadline are seeing higher refunds, while gross payments are down 52% year-over-year.

The increased refunds (+33% YoY) and the decreased gross payments (-52%) appears to stem, at least partially, from the incentives created by federal tax reform. Individual filers that benefited from the doubling of the standard deduction may have filed earlier this year, while filers that saw a tax liability increase may be waiting to make their final payment until April. A snapshot of the revenue picture follows.

For more, read our monthly revenue snapshot, here

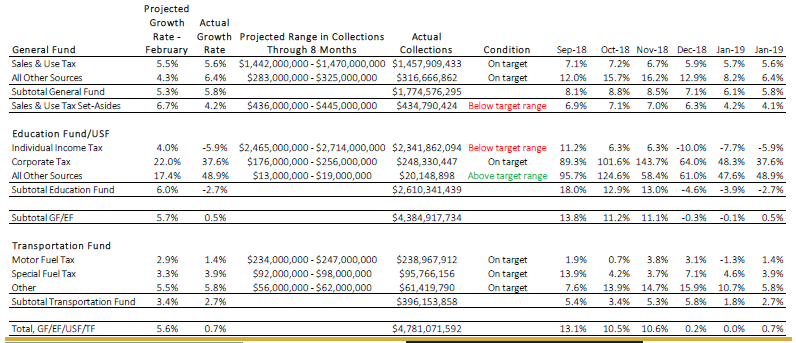

Slight Improvement in Revenue Growth through February

The Tax Commission released their monthly revenue report (TC-23) earlier today. Through the first 8 months of FY 2019, according to the report, the revenue sources within the General Fund are on Target.

Income Tax Withholding is still below Target range at -5.9%. However, the rate is an indication of increased funding compared to December 2018 (-10.0%) and January 2019 (-7.7%). As Income Tax Withholding continues to reach the Target range, overall Education fund collections have inched closer to the target range as well, going from -3.9% in January 2019 to -2.7% in February 2019.

Year-over-Year (YOY) growth in the General and Education Fund revenue collections is at 0.5%. This is the first positive YOY growth rate in the General and Education Fund revenue since November 2018.

A snapshot of the collections is shown in the figure below:

More details of the revenue picture through 8 months is available here.

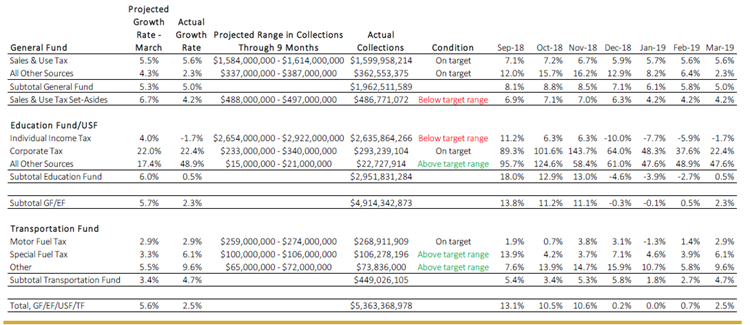

Revenue Collections Still Below Target Despite Growth in March

The Tax Commission’s TC-23 report, which captures a snapshot of revenue collections through the first 9 months of fiscal year 2019, shows that Income Tax Withholding is still below Target range at -1.7%.

Throughout the year, this funding has been volatile as year-over year (YOY) revenue has gone from a growth rate of 11.2% in November 2018, followed by a negative growth rate in December 2018 (-10%). April’s report, which will be published during the third week of May, should provide a reasonable projection for Income Tax revenue by the end of the year.

In addition to Income Tax revenue, sources within the General Fund are on target. There has been little fluctuation in the General Fund rates throughout the year as revenue collections have remained consistent.

Overall, YOY growth in the General and Education Fund revenue collections is at 2.3%. This is an increase in funding compared to last month’s report (0.5%).

A snapshot of the collections is shown in the figure below:

More details of the revenue picture through 9 months is available here.

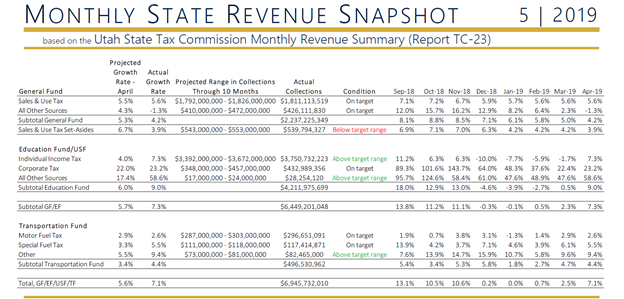

Strong Final Payments Highlight April

Earlier this week, the Tax Commission released the TC-23 report for the month of April. Exceeding the current revenue target of 5.7%, General and Education Fund revenue collections totaled $6.4 billion through the first 10 months of FY 2019, representing a year-over-year (YOY) growth of 7.3%.

The strong surge in April revenue collections were due to final income tax payments within the Education Fund. In December and January, revenue collections were below target range at -4.6% and -3.9%, respectively. This was due in large part to incentives created by federal tax reform, thus yielding lower payments compared to the previous year. With steady growth in the Education Fund during February and March, the YOY growth in the month of April exceeded projected growth rates as strong final income tax payments were made.

While the General Fund is below target, the revenue collections are still within target range at $2.2 billion through the first 10 months of the current fiscal year. Overall, consistent General Fund revenue collections, accompanied by increased growth in the Education Fund, indicate that total revenue collections for FY 19 are on target.

A snapshot of the collections is shown in the figure below:

More details of the revenue picture through 10 months is available here

Local Governments Address Long-Term Fiscal Stability Amid Population Growth

Utah’s population grew nearly 15% this decade, ranking No. 1 in the nation.1 By 2060, Utah’s population is projected to nearly double. The dramatic growth is a cause for concern for local governments across the state as communities address the fiscal challenges and quality of life for existing residents.

The Utah Foundation recently published the report, Building a Better Beehive: Land Use Decision Making, Fiscal Sustainability and Quality of Life in Utah, which explores these challenges. The report highlights five strategic categories to overcome the challenges of growth in our state:

- Promoting efficient land use.

- Expanding transportation options.

- Preserving green spaces and natural assets.

- Preserving and improving community character.

- Avoiding undue taxpayer subsidy of new growth.

Promoting Efficient Land Use: While density is often a matter of concern for existing residents, local governments can use density to their advantage to increase local tax revenue while providing opportunities for both new and existing residents and businesses within the community. With a greater emphasis on mixed-use developments, local governments throughout Utah can create urban communities that are appealing and safe while reaping a stronger tax revenue return per square foot.

Expanding Transportation Options: According to a Utah Foundation survey, nearly 76% of local governments noted that the need to increase road capacity was one of the greatest impediments to growth. As Utah’s population continues to grow, roads across the state are increasingly prone to traffic. To combat traffic congestion along the Wasatch Front, the report suggests that state and local government agencies work together to utilize transit-oriented developments that improve accessibility to public transit while developing mixed-use communities that promote quality of life through pedestrian transportation options, including bike paths, sidewalks, and trails.

Preserving Green Spaces and Natural Assets: Utahns are committed to preserving the natural surroundings of the state. Outdoor recreation is essential to the quality of life experienced by Utah’s citizens. Through efficient urban planning, cities along the Wasatch Front can accommodate the growing population while easing pressure on both recreational and agricultural lands. Maximizing space within denser areas can lead to local governments developing “green spaces” to increase the quality of life for urban residents while bolstering nearby property values, thus increasing tax revenue.

Preserving and Improving Community Character: To preserve and improve community character, local governments are encouraged to help citizens and businesses collaborate to ensure that planning efforts offer attractive neighborhoods and community gathering places. By undertaking projects, such as revitalizing historical sites, constructing efficient public parking, and designing an aesthetically appealing landscape, communities can increase the quality of life while tackling the fiscal challenges of population growth.

Avoiding Undue Taxpayer Subsidy of New Growth: As commercial developments grow in communities throughout the state, local governments are faced with fiscal challenges regarding the costs of services and infrastructure for new developments. Local governments must find a balanced approach to utilize impact fees to ensure that current residents do not subsidize new developments. It is important that local governments evaluate impact fees regularly to ensure a strong tax base while welcoming commercial developments that enhance the community.

Addressing the challenges of Utah’s growing population will be a significant priority for policymakers in the foreseeable future. Local governments will need to promote efficient land use by emphasizing mixed-use developments to meet the needs of citizens, businesses, and communities in our state. Transportation demands can be satisfied by improving existing infrastructure and expanding transportation options in our communities. As Utah’s population continues to grow at a high rate in the next 40 years, local governments will continue to work with community leaders to meet the growing demands of the state while preserving the quality of life.

The full report can be found here

- Davidson, L. (2018, December 20). Utah ranks No. 1 for population growth this decade - adds nearly 400K new residents. Retrieved June 11, 2019, from https://www.sltrib.com/news/politics/2018/12/19/utah-ranks-no-population/

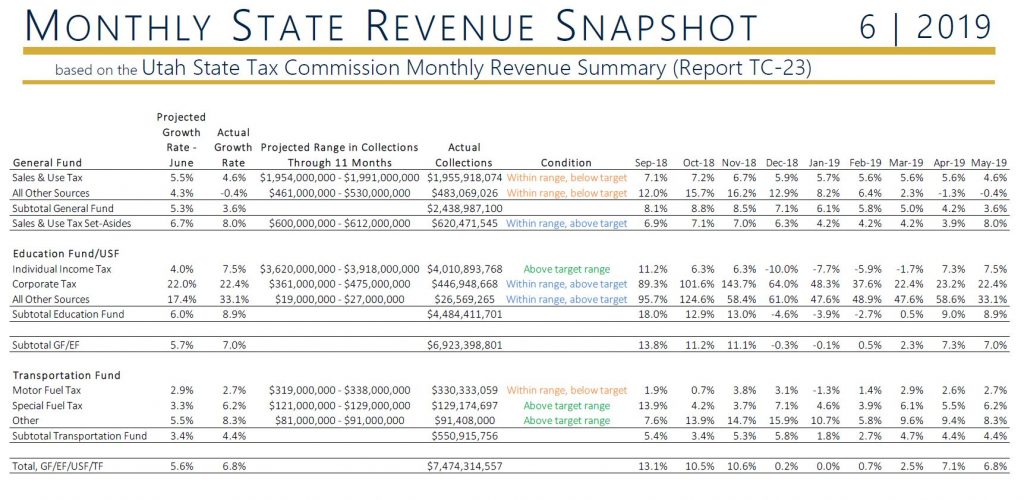

Strong Income Tax Lifts State Revenue Collections Despite Declining Growth Rates

Combined General and Education Fund revenue collections for the current fiscal year (2019) totaled $6.9 billion through the first eleven months. That represents year-over-year growth of 7.0%, exceeding the current revenue target of 5.7%. This despite a slight decrease in the growth rate compared to April.

Collections for the General Fund, however, fall short of the 5.3% point target used in budgeting. For the first eleven months of fiscal year 2019, General Fund revenue has grown only 3.6%. While collections are still within striking distance of the May target, for the seventh consecutive month the General Fund’s year-over-year growth rate has declined. Overall, since reaching 8.8% in October 2018, the growth rate has decreased 5.2%.

Due to another strong year in the Education Fund, though, combined General and Education Fund revenue is above target. Education Fund collections currently reflect an 8.9% growth rate compared with the year-end target of 6.0% year-over-year growth.

A snapshot of the collections is shown in the figure below:

More details of the revenue picture through eleven months of fiscal year 2019 is available here

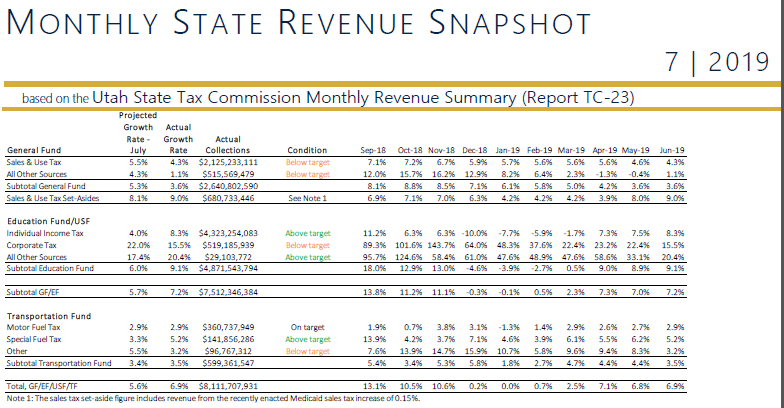

Strong Income Taxes Bail-out Sales Tax Through 12 Months of FY19

Despite a probable deficit in the General Fund, the Utah State Tax Commission's latest report on revenue collections for twelve months of fiscal year 2019 suggests that Utah may have a combined General and Education fund revenue surplus of nearly $100 million at year-end. While collections to the sales-tax backed General Fund lag estimates by more than $40 million, strong income tax collections have boosted the Education Fund to nearly $140 million above projections. Revenue to the General and Education Funds combined totaled $7.5 billion through twelve months, and exceeded the consensus revenue target of 5.7% with a year-over-year (YoY) growth rate of 7.2%.

General Fund collections reached a YoY growth rate of 3.6%, pacing behind the consensus target of 5.3%. Preliminary General Fund collections totaled $2.6 billion in FY 2019. The relatively low growth rate in General Fund collections is strongly influenced by the sales tax growth rate of 4.3%, which fell below the consensus target rate of 5.5%. Preliminary measures estimate the General Fund will end the fiscal year in a $43 million revenue deficit.

The 2019 fiscal year featured strong collections in the Education Fund with a projected surplus of $140 million. Behind healthy performances in individual and corporate income taxes, the State’s Education Fund reached a total of $4.9 billion in FY 2019, representing a YoY increase of 9.1%.

These figures will all change as state accountants close-out the books for fiscal year 2019. Final collection amounts and resulting revenue surplus/deficit figures will be released in September.

A snapshot of current collections is shown in the figure below:

More details of the revenue picture through fiscal year 2019 is available here

Revenue Surplus Sets the Stage for Tax Reform

The year-end numbers are in

In Fiscal Year 2019, the revenue surplus to the education fund was $134 million. After adjustments (such as putting money in the rainy-day fund), the available balance is $107 million. The General Fund, supported mostly by the sales tax, ended the year at a deficit of $38 million, which was reduced to a $22 million deficit after adjustments. Adjustments to the General Fund include balances which were left unspent by agencies during the fiscal year. The Transportation Fund, furnished by motor fuel tax, diesel tax, and registration fees, among others, ended the year at $6 million above the target.

For the full summary of Fiscal Year 2019: click here.

A decent start to the new fiscal year

The aggregated total revenue amongst all funds is on track with the unadjusted projection made last February, at a year-over-year (YoY) growth rate of 3.6% (the current target is 3.5%). After the Governor releases his budget proposal in December, revenue targets will be adjusted for the remainder of the year. As a note, revenue collections are typically volatile during the first half of any given fiscal year; because of this, caution should be exercised when interpreting these early-year revenue figures.

Comparable with Fiscal Year 2019, the revenue postings to the General Fund are roughly 2% below the current target, the Education Fund is approximately 1% above first quarter projections, and the Transportation Fund is performing about 3% above target. The growth in the Transportation Fund is being spurred largely by sources other than the Motor Fuel Tax, which showed a negative growth rate of 2% during the first three months of the fiscal year.

For the September report: click here.

Income Tax Continues to Outpace State Sales Tax through Q1

State Revenue Growth Higher than February Projections

In the first quarter of the Fiscal Year, income tax grew 11.3% which represented a $135 million dollar increase over the first quarter of last year. Nominally, state and local sales taxes each grew by similar amounts, at $80 million and $81 million, respectively, over the previous fiscal year. The special fuel tax (which includes diesel) continued to perform well, posting 15.1% year-over-year growth, and furnishing most of the growth to the Transportation Fund. Corporate Taxes are notably behind last year, with a 28.6% reduction representing a $44 million decline in revenues. In terms of percent change, Mining Severance Tax demonstrated the largest growth with a 37% increase, though this only represented a $1.2 million increase in collections over last year. As always, revenue growth rates are highly volatile during the first half of any given fiscal year and caution is advised when drawing conclusions based upon these figures.

Revenue to both the General and Education Funds totaled $2.4 billion through the first four months of the Fiscal Year 2020, representing a year-over-year growth rate of 5.5%. This growth is about 2% higher than the unadjusted consensus revenue target from February. The targets will be updated later this month when the Governor’s budget is released and will also incorporate year-end numbers from Fiscal Year 2019.

For the full November report: click here.

For the full Quarter 1 Revenue Summary report: click here.

Revenue Collections in-line with Latest Estimates

First Half of FY 2020 in the Books

Reports for December and January show both General and Education Fund revenues coming in on-target, with collections for the first half of the year slightly higher than targets adopted in November. December’s numbers showed General Fund sales-tax collections slightly below the estimate, while January’s revenue performance was slightly above. Both months are within expected range projected by staff economists. The income tax-backed Education Fund was higher than point estimates in both months, but still within anticipated ranges. Consistent with longer-term trends, Education Fund growth rates continue to exceed General Fund growth rates, though the difference moderated somewhat in December due to holiday consumption patterns.

The first six months’ General Fund sales tax collections finished at 6.7% growth, 1.6% above the annual growth target of 5.1%. However, because the first six months of the Fiscal Year includes holiday sales, it’s ill-advised to compare the first six months to the entire year. Typically, sales tax growth rates tend to moderate over the course of the year. For example, in the first six months of Fiscal Year 2019, General Fund sales tax grew by 5.9% compared to a final growth rate of 4.8% for the year as a whole. For these reasons, caution should be used when drawing conclusions from the first half of any year’s tax collections. Additionally, volatility was expected this year due to policy implementation, such as that of third-party collection of remote sales.

For the December Revenue Snapshot: click here.

For the Fiscal Year 2020 6-month Revenue Snapshot: click here.

Sales Tax Growth Improving, Not Enough to Close Gap in Education and General Funds

On Thursday (Feb. 20th), the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget and the Legislative Fiscal Analyst released their updated 2020 Consensus Revenue Estimates. These estimates, along with the Tax Commission’s TC-23 Report for revenue collections to date, paint a picture of state financial status to date, along with expectations for the next 16 months. Both reports reflect a disparity in both total revenues to the General and Education Funds, as well as future projected growth rates.

The Tax Commission reports that collections from sales and use tax totaled $1.8 billion during the first seven months of Fiscal Year 2020, which is the largest contribution to the General Fund. Last fiscal year, the General Fund collections totaled $2.6 billion, a whopping $2.2 billion less than Education fund revenues. This discrepancy between funds is expected to grow to $2.5 billion by June of 2021, according to the Consensus Revenue Estimates.

For the current Fiscal Year, the Education Fund is expected to see an increase in ongoing available revenue of $518 million, which represents a $77 million boost over November’s estimate. This is on top of a projected one-time increase to the Education Fund of $323 million, resulting from expectations of strong income tax collections through the end of the fiscal year. GOMB and LFA agree that income taxes will continue to increase through the end of the Fiscal Year, moderating to 6.2% growth in FY 2021.

The reports referenced in this post are available at the following links:

Revenue Snapshot

TC-23 Report

Consensus Revenue Estimates

Revenues Still On-track, but Don’t Yet Reflect Pandemic’s Impact

Through the end of February, revenues from all taxes were on target, representing an increase of $571 million over FY 2019. Sales and use tax grew by 7% over the previous year, and income tax collections were 8.9% higher than February 2019. However, impacts to revenues from COVID-19 related business closures and layoffs are not reflected in these collections due to timing differences in reporting and collections. Some of those dampening effects may be seen in the April TC-23 report, which will report on March activity. However, it will likely be May or June before tax collections will reflect the actual impacts to revenue from recent changes in the economy. In the meantime, weekly unemployment insurance claim reports produced by the Division of Workforce Services provide the closest to real-time indication of economic activity.

It’s worth noting that upon entering this time of economic contraction, Utah was ranked first for economic momentum in both the last quarter of 2019 and first quarter of 2020 according to State Policy Reports. Utah has also incorporated into its normal budgeting process Stress Testing to better understand and prepare for unforeseen downturns in the economy.

The reports referenced in this post are available at the following links:

March TC-23 Report

March Revenue Snapshot

DWS Unemployment Data

Collections Hold Steady as the Legislature Prepares to Weather the Storm

The April TC-23 report released by the Tax Commission reports revenue collections to the General, Education, and Transportation Funds are all on target with consensus projections through the first nine months of the fiscal year. The April report shows collections through March, for sales and wages that occurred in February. For the third month straight, the General Fund posted a 7% growth rate over the previous fiscal year, which may represent strong collections from online sales taxes. The Education Fund showed increased collections of 7.3% over FY 2019, as income taxes remained solid through the third quarter of FY 2020.

Undoubtedly, next month’s report will show a much different picture of revenue collections. State and county directives to stay at home will likely impact the transportation fund, delayed income tax collections will impact the education fund, and closed businesses are expected to result in fewer sales tax collections than were projected prior to the pandemic.

The Legislature will enter its first-ever electronically held session on Thursday, April 16th. This particular session is also unique because it was called by the Legislature itself. The special session will address federal stimulus packages and budgetary actions to cope with expected revenue shortfalls to the state’s tax collections. While the full extent of revenue changes will be measured in the coming months, projections from Legislative and Executive Branch economists are assisting the legislature in taking action to help Utah get back on track.

The reports referenced in this post are available at the following links:

April Revenue Snapshot

TC-23 Report (Period 9, FY 2020)

Income and Fuel Taxes Begin to Show Pandemic Effects

On Tuesday, May 12th, the Tax Commission released their TC-23 Revenue Summary Report for the month of May. Readers may recall that the April TC-23 report was summarizing collections made in March, for sales and wages which took place in February. Because of the lag between collections and reporting, this month’s Revenue Summary is the first look at measuring the impacts of the pandemic on tax revenues; including changes in travel, income, and sales which occurred in March.

Revenue sources to the General Fund were the least impacted by the pandemic during the reporting period. Sales and Use Taxes were up 6.7% over the previous Fiscal Year, exceeding the February consensus target of 6.2%. Through the first 10 months of FY 2020, the General Fund reached $2.4 billion in collections. Online sales tax revenues have likely helped the General Fund collections during the state’s required business closures. We expect this source will begin to show signs of COVID related softness next month.

The Education Fund targets in this report are adjusted to reflect the delay of income tax filing deadlines from April 15th (during Fiscal Year 2020) to July 15th (Fiscal Year 2021). After timing adjustments were made to revenue targets, actual Education Fund collections were 2.8% lower than the February consensus target. Income tax collections were 14.4% below the previous Fiscal Year, as a raw comparison ignoring changes to the normal tax cycle.

Combined, General and Education Fund collections in April are 7.1% below prior year collections and 1.7% below the target adjusted for delayed filing of income taxes. Transportation Fund revenues were below the consensus target from February, but remained 1.2% higher than FY 2019. Perhaps not surprising, Aviation Fuel tax was down -6.5% from the previous fiscal year. Consensus revenue targets will be updated in early June to capture new projections for the Utah economy resulting from the pandemic.

The reports referenced in this post are available at the following links:

May Revenue Snapshot

TC-23 Report (Period 10, FY 2020)

Pandemic Impacts Take Shape as Fiscal Year Comes to a Close

The Utah Tax Commission released its TC-23 Revenue Summary Wednesday, June 17th, 2020, detailing the actual collections through 11 months of Fiscal Year 2020. As expected, individual income taxes are down, partially due to the shift in timing of income tax collections from FY 2020 to FY 2021, as well as the effects of COVID-19. While consumption patterns may have changed, sales and use tax revenues actually increased 9.2% over the same collection period in FY 2019.

The State Revenue Snapshot published by the Legislative Fiscal Analyst and the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget compares the revenues reported by the Tax Commission to economic projections upon which state budgets are based. The latest projections include adjusted expectations for income taxes associated with an extended filing date, and an attempt to capture the impact of reduced income tax revenue associated with decreases in employment and wages. The snapshot reports Education Fund revenue sources down (12.6%), which exceeds the consensus projections by (1.1%). Revenue sources to both the General and Education Funds are down (6.5%), representing a (1.0%) greater decline than was forecasted. Defying expectations, the Transportation Fund revenue sources actually increased 0.1% over the previous fiscal year.

The final period of any fiscal year is typically volatile due to final tax payments and year-end adjustments. Revenues reported in this month’s TC-23 report and analyzed in the Revenue Snapshot represent wages and sales which took place in the month of May. The course of the pandemic and associated recession will determine the final, year-end numbers for tax revenues reported next month. The projections included in the Revenue Snapshot assume limited adverse impacts in the fall associated with the pandemic, and carefully estimate impacts of Federal stimulus money. These projections will be updated as better information is available.

The reports referenced in this post are available at the links below:

June Revenue Snapshot

TC-23 Report (Period 11, FY 2020)

Federal Stimulus Appears to Band-Aid Revenues through close of Fiscal Year 2020

The preliminary TC-23 Revenue Summary Report for twelve months of FY 2020 was released by the Tax Commission Thursday, July 16th, along with the Revenue Snapshot report from the Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst (LFA) and the Governor’s Office and Management and Budget (GOMB). The TC-23 is preliminary in that it will be modified in the next few months to include final adjustments made at year-end closing. The targets reflected in the Revenue Snapshot reflect adjusted expectations due to the pandemic as well as delayed income tax collections.

Sales and Use Tax, a primary revenue source to the General Fund, rebounded during the month of June. In contrast to collections from April and May, June represented the largest year-over-year growth for any single period of the fiscal year. This increase may be due to the influences of pent-up demand, federal stimulus actions, and collections of online sales in the wake of reduced foot traffic to stores.

As the Education Fund awaits final income tax collections, preliminary figures paint a slightly more optimistic picture than was originally anticipated due to pandemic-associated reductions in employment. The Education Fund reached $4.4 billion at the time of reporting; this figure is expected to increase as final collections and year-end adjustments are made.

The unprecedented circumstances of COVID-19 are further complicated by the influence of federal stimulus packages, making economic forecasts very challenging. Despite this, Education Fund as well as General Fund collections are within the FY 2020 target range projected in June by LFA and GOMB analysts. Fiscal Year 2021 revenue performance remains extremely uncertain due to the unknowns surrounding the income tax filing delay and future of federal economic stimulus.

The reports referenced in this post are available at the links below:

Year End Revenue Snapshot FY 2020

TC-23 Revenue Summary (Year End, FY 2020)

Revenue Through Q1 Boosted by Online Sales and Federal Stimulus

Federal Stimulus Helps FY 2020 End Better than Expected

Earlier this month, the Tax Commission released the final TC-23 Revenue Summary for Fiscal Year 2020. The revenue decline to the Education Fund was less severe than previously projected in June, dropping 10.1% compared to the projected 11.6% decline. The General Fund ended the year with 7.4% positive growth. During November’s Executive Appropriations Committee, the Division of Finance will announce year-end figures for the both the Education Fund (which include adjustments such as putting money aside in the rainy-day fund) and General Fund (which include adjustments such as unspent appropriated funds). Although the preliminary outlook for revenues to both state funds appears optimistic, the better-than-anticipated outcomes are likely the result of income tax delays and significant federal stimulus actions, the future of which remains largely uncertain. As Fiscal Year 2021 unfolds, staff economists will have a better picture if the budget reductions from earlier this year will be sufficient to balance the budget.

Q1 of FY 2021 Provides Largely Uncertain Outlook

A cursory review of the first quarter revenue summary for Fiscal Year 2021 will indicate that revenues are on target for all state funds, with the General Fund posting a growth rate of 8.3%, and individual income taxes a whopping 83.5%. In reality, sales tax growth rates are skewed in an upward direction because the first quarter of Fiscal Year 2020 did not include online sales tax for marketplace facilitators (such as eBay); these collections went into effect in October of 2019, so the year-over comparison is skewed until second quarter figures come in. Further distortions result from federal stimulus actions, which have buoyed both sales and income taxes. To date, federal intervention has totaled nearly $2.6 billion, or roughly 1.4% of Utah’s Gross State Product (GSP). A final obscurity unique to FY 2021, is provided by the income tax timing delay. Because Income Tax collections were made in July (usually posted in April) there is an artificial spike to the Education Fund from revenues that should have been collected in FY 2020.

As with the first quarter of any fiscal year, revenue collections are typically volatile and because of this, caution should be exercised when interpreting these early-year revenue figures. It should also be noted that tax collections lag economic activity by up to four months depending on type, so Q1 revenues are indicative of sales that took place during the summer.

The reports referenced in this post are available at the links below:

Final Revenue Snapshot FY 2020

TC-23 Revenue Summary (Final, FY 2020)

First Quarter Revenue Snapshot FY 2021

TC-23 Revenue Summary (Q1, FY 2021)

Despite Future Uncertainty, Revenues Continue Upward Growth

On Monday, November 16th, the Tax Commission released the TC-23 revenue summary, along with the GOMB/LFA Revenue Snapshot, detailing collections through the first four months of Fiscal Year 2021. Similar to last month’s report, important caveats exist within the income and sales collection figures, and also year-over-year comparisons. October of 2019 was the first month that the state collected sales tax from marketplace facilitators (such as eBay); the lag between collections and reporting leaves sales tax with a somewhat artificially inflated growth rate, posting a 10.2% increase over the same period last fiscal year. This does provide the state with an idea of the effect of marketplace facilitators, which may have impacted sales tax revenues more than was previously anticipated. Next month’s report will provide a clearer view on year-over-year comparisons.

The Education Fund revenues from income taxes totaled just over $2 billion through November 1st; the growth rate moderated slightly, dropping by 30 percentage points compared to last month. It is expected that the income tax growth rate will continue to temper over the course of the fiscal year, as these figures include income taxes which would have normally been received during the previous fiscal year.

Transportation Fund revenues, having fewer provisos than the other two state funds, are trending positive and are within the expected target range, posting a 4.9% growth rate over last year’s collections.

Current revenues to both the Education and General Fund tell a story of economic activity which took place in previous months, due to the timing delay in collections and reporting. Expectations for both sales and income tax are that the growth rates will normalize to within target ranges. The outlook for federal stimulus and the course of the pandemic will also heavily influence these two state funds.

The reports referenced in this post are available at the links below:

November Revenue Snapshot FY 2021

TC-23 Revenue Summary (Period 4, FY 2021)

Rollercoaster Year Ends on a Positive Note for Revenue Collections

On December 16th, the Tax Commission released the TC-23 revenue summary detailing the first five months of collections to state funds. The Education Fund remains a bit enigmatic, due to inflating factors (including federal stimulus and the income tax timing delay) which leave current year income tax collections trending off the charts. The General Fund posted a 4.9% growth rate from all sources, with this month marking the first period that the impacts of online marketplace facilitators can be compared between FY 2020 and FY 2021. Preliminary numbers from the Tax Commission indicate that marketplace facilitators brought in around $3.8 million more revenue to the state in October 2020 than in October 2019. The additional sales tax dollars from marketplace facilitators brought in an estimated $65.6 million during all of FY 2020, and to date have generated an estimated $47.8 million in FY 2021.

As expected, sales tax growth through the end of November moderated slightly from the previous reporting period, posting 9.6% growth over FY 2020 as compared to 10.2% last month. Other revenue sources to the General Fund are down, including severance taxes from mining and oil and gas, which posted a combined $10.9 million decrease in revenue compared to this time last year.

Income tax revenue collections to date are $885.3 million higher than last December, spurred mostly by the timing delay in income tax payments which postponed an estimated $785 million to the current fiscal year. Despite much uncertainty in how income taxes will continue to perform for the duration of the fiscal year, it appears that growth rates remain positive to the Education Fund. Estimates from Legislative, Governor's Office, and Utah Tax Commission economists indicate that underlying the obscurity provided by the income tax delay is a 1.5% year-over-year (YoY) growth in revenue to all sources in FY 2021, and 6.5% YoY growth into FY 2022.

While the future of federal aid remains undecided, legislative economists estimate that previous pandemic stimulus packages have translated to $330 million in income tax revenue and $120 million in sales tax revenue in Utah. In the upcoming General Session, this combined roughly $450 million will be considered one-time revenue for budgeting purposes. Consensus revenue estimates released at the December Executive Appropriations Committee are contingent on several factors, including future federal aid and vaccine outcomes.

The reports referenced in this post are available at the links below:

December Revenue Snapshot FY 2021

TC-23 Revenue Summary (Period 5, FY 2021)

Revenue Forecasts Improve, though Uncertainty Lingers

On February 19th, the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget (GOMB), Utah Tax Commission, and the Legislative Fiscal Analyst (LFA) released their updated Consensus Revenue Estimates for available one-time and ongoing state fund revenues. These updated estimates from the December 2020 forecasts paint somewhat optimistic expectations for the next 16 months; with FY 2021 revenues finishing stronger than previously anticipated, followed by more moderate revenues in FY 2022 under the expectation of exhausted federal stimulus and uncertainty about broad economic recovery. For the Legislature’s budgeting process, this forecast translates to a total of $1.4 billion in available new one-time funding ($315 million above the December forecast), and $205 million in available new ongoing state funds ($112 million above the December forecast). By comparison, the requests to date from appropriations subcommittee priorities, fiscal note bills, and other requests total nearly $2 billion one-time and $400 million ongoing.

The Tax Commission’s TC-23 Reports, detailing cumulative revenue collections through January and February, are sufficient to support a strong finish to FY 2021 revenues, though collections for February are somewhat short of the new targets. January’s report, including roughly half of the fiscal year, shows sales tax collections up 10.2% over FY 2020. In February, this trend continued, with sales tax posting a 10.0% increase over the same period in the previous fiscal year. These strong sales tax revenues are primarily driving the General Fund figures, which posted an actual year-over-year (YoY) growth rate of 5.9% in January, and 5.7% in February. Sales and use tax set asides, which include things like Medicaid Expansion and Water Infrastructure, grew 7% over the previous fiscal year. Sales and use tax set asides have a different growth rate than the General Fund because of the specific categories of sales which are taxed, and also because some the set asides have statutory collection caps.

Education Fund sources continue to remain inflated over previous years’ collections, due partially to the income tax deadline extension shifting approximately $770 million from FY 2020 to FY 2021. Corporate tax growth increased from January to February, which could be an indication of seasonal hiring patterns as well as corporate confidence in the economy, as Utah has recovered the number of jobs which were lost during the pandemic. Income tax growth rates have continued to temper (as expected) over the course of the fiscal year, slowly approaching the consensus target of 23.6%.

It is worthwhile to remind readers of the lag between collections and reporting, with January’s report detailing collections made in December, for sales and wages that took place in November. This means that May will be the first time that economists can compare impacts of the pandemic (pre-federal stimulus) to the current fiscal year for the General Fund. Education Fund comparisons may be more appropriate in a fiscal year with typical timing for income tax collections.

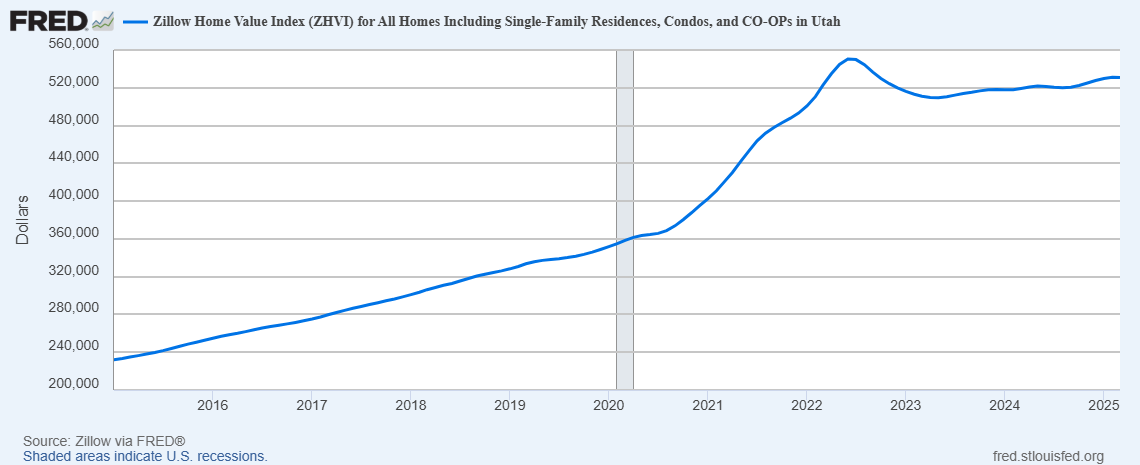

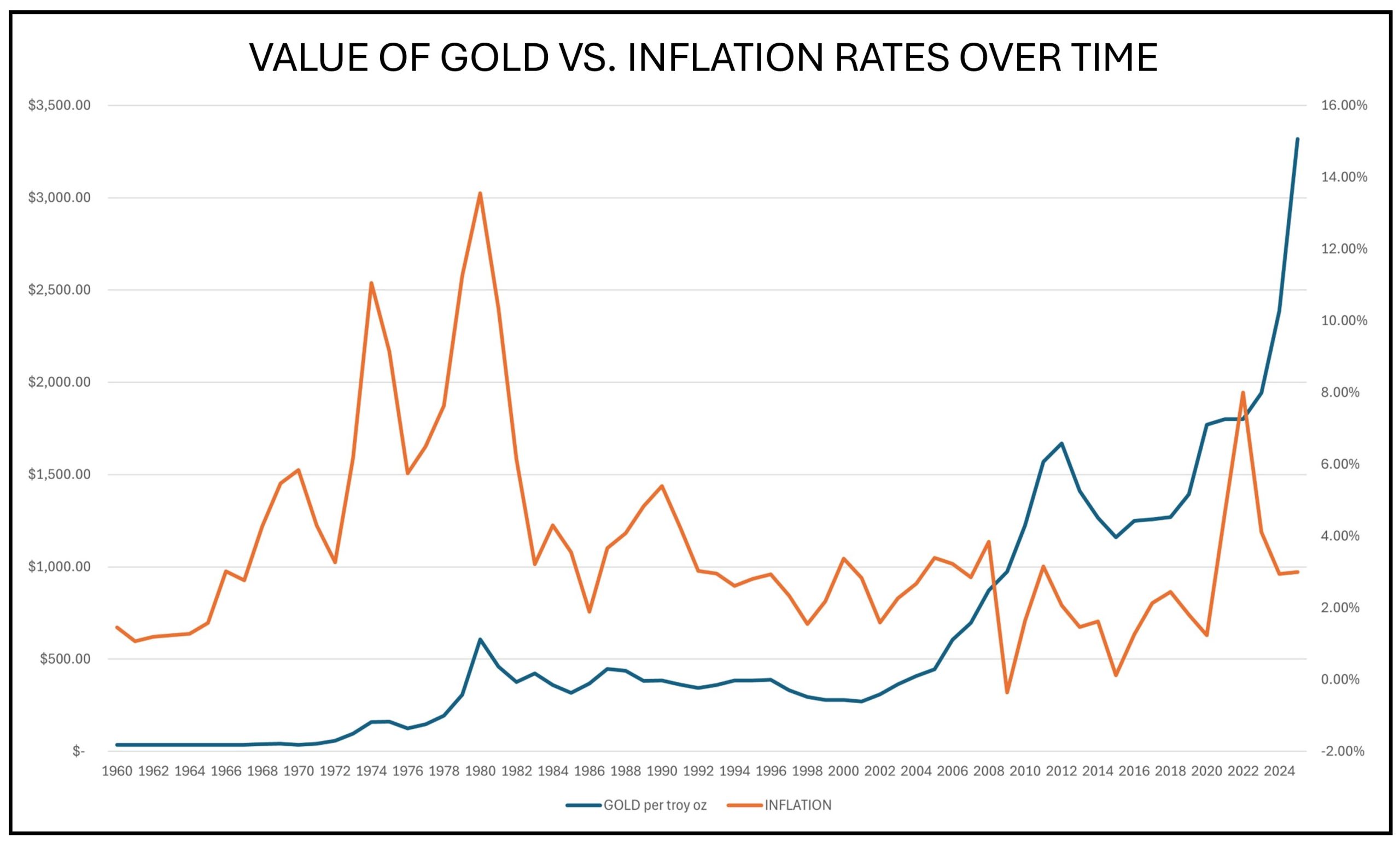

While legislative economists are cautiously optimistic, they offer some important caveats to the positive outlook through the fiscal year, including that forthcoming federal stimulus will likely be the final installment of pandemic related funding for states. They note there may also be slower recovery for the hardest-hit sectors of the economy, in contrast to the state’s revenues in aggregate. As a final caution, legislative economists observe that current conditions show potential for increased inflation, which could reduce consumer spending, and any increase in interest rates may cause certain sectors (such as housing) to slow.

The reports referenced in this post are available at the links below:

January Revenue Snapshot FY 2021

TC-23 Revenue Summary (Period 6, FY 2021)

February Revenue Snapshot FY 2021

TC-23 Revenue Summary (Period 7, 2021)

Consensus Revenue Estimates

It's a Wrap! The 2021 General Session Comes to a Close

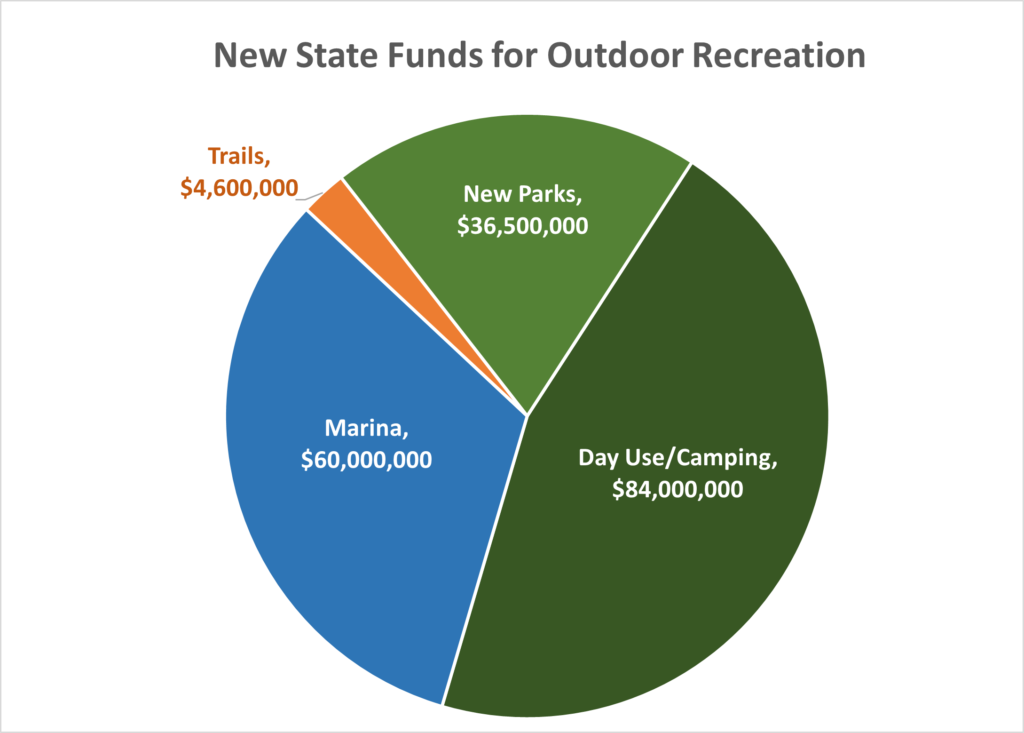

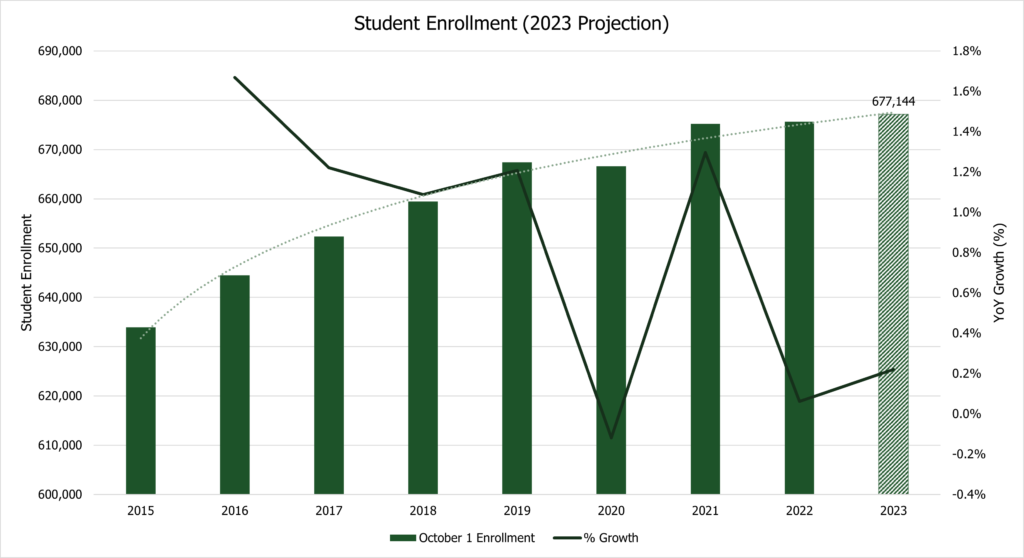

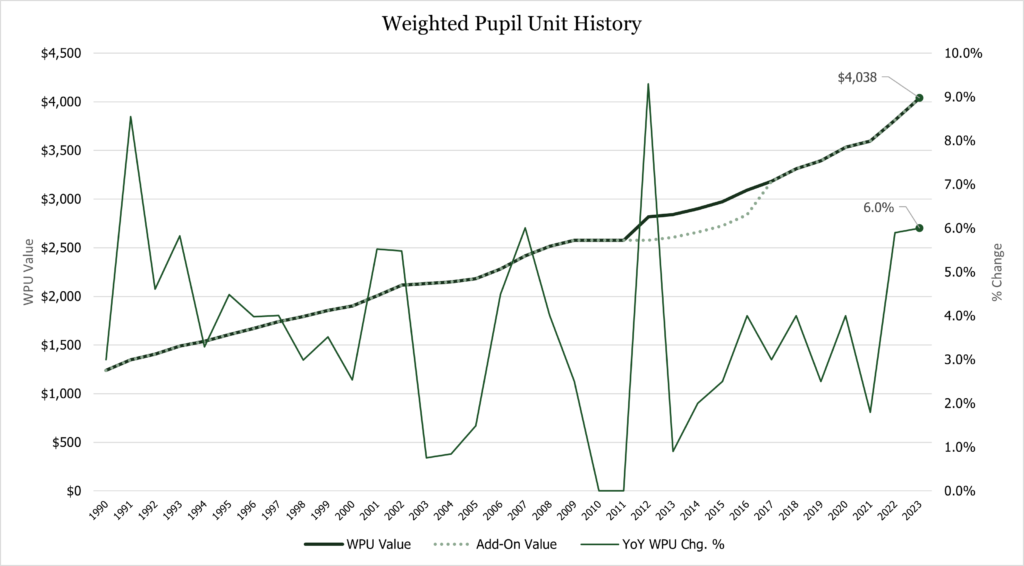

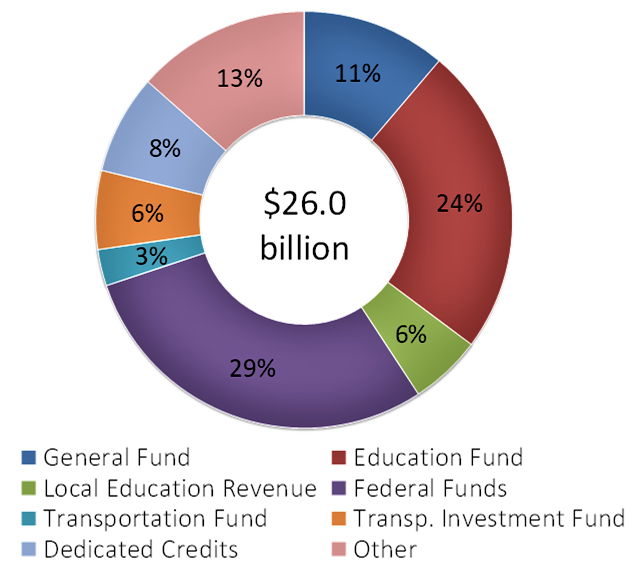

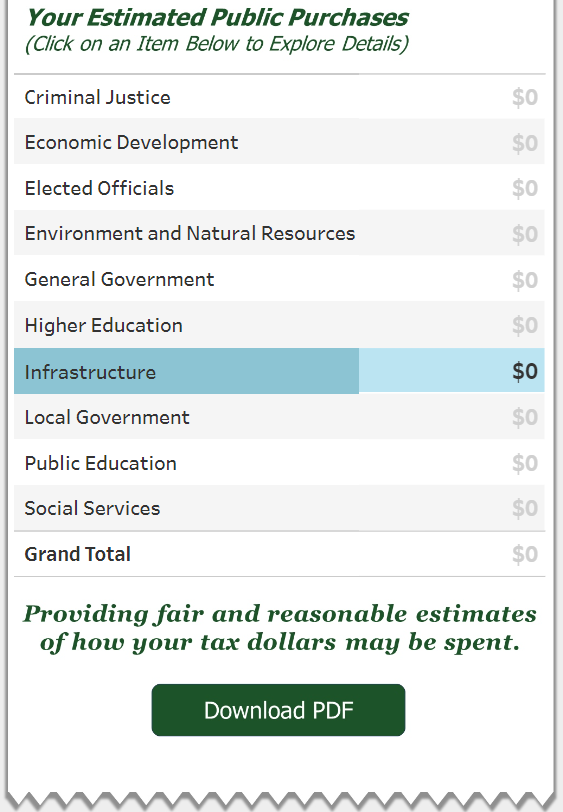

The Utah Legislature adjourned on the 45th day of a General Session which was groundbreaking in many ways. Utah’s $23.5 billion budget for Fiscal Year 2022 includes $10 billion in spending from the General and Education funds, and nearly $7 billion from Federal funds. During a pandemic, the Utah legislature was able to fund very notable investments for the state, which include:

- -Nearly $100 million in tax cuts,

- -Public education enrollment growth and inflation (and restored a 6% increase in per-student funding),

- -$121 million for public school teacher stipends,

- -$127 million ongoing for public education economic stabilization,

- -Nearly half a billion dollars for public education,

- -A more than 9% increase for higher education,

- -$200 million in new cash-funded building and land purchases,

- -$1.1 billion for roads and transit,

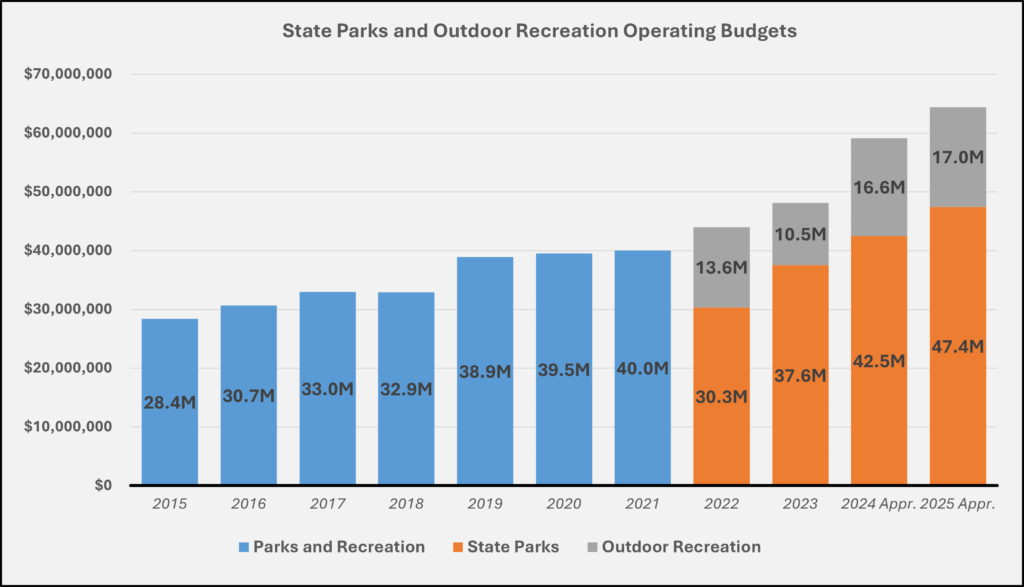

- -$36.5 million for two new state parks (a third of that with investment earnings and not taxes),

- -$110 million to renovate existing state parks and create new trails, bike lanes, and pedestrian pathways,

- -$56 million for wildfire suppression,

- -3% raises for state and higher education employees,

- -Targeted increases for front-line workers in social service agencies, public safety, and corrections,

- -Fully funded growth and inflation in Medicaid (and fixed a $56 million structural imbalance in Medicaid expansion),

- -$26 million in new ongoing funding to enhance mental health services,

- -$50 million in tax proceeds, securing a total of $730 million in combined public-private funding for housing and homelessness, and

- -$250 million to address the pandemic, including economic development assistance, rural broadband expansion, testing, and vaccine distribution.

There are a number of resources available for the public and legislators to understand more about Fiscal Year 2021 and 2022 funding:

Budget Quick Facts – A pocket-sized guide to the budget.

Budget in Bullets – Highlights of the state budget overall as well as detail for each appropriations subcommittee.

DataViz – An interactive graphical representation of the budget. View the budget by sources, uses, and new money. Click a bubble to see how that item has changed over time, and in what bills it changed. Search for budget requests and find where it exists in appropriations bills.

Compendium of Budget Information (COBI) – A complete guide to the Utah State budget. Find budget requests on the Issues tab, and Line item/program budgets on the Financials tab.

Revenue On-Pace through Month Eight

The Utah State Tax Commission released updated revenue collection data today. For the first eight months of fiscal year 2021, General and Education Fund revenue is slightly below our latest point projections, but well within range to hit our target at year-end. Sales tax continues to be stronger than anticipated. Income tax is almost exactly on target. Other GF/EF sources lag projections a bit, but change dramatically at year-end. We anticipate the year-over-year income tax growth rate will accelerate in the next two months as "normal" collections are compared with last year's delayed collections.

Month eight Transportation Fund revenue lags behind our point target for the year as a whole, but is still within range. In the next few months we'll know more about whether driving habits changed by the pandemic will result in lower than projected gas tax collections.

For a more detailed summary, see our monthly snapshot. For all the gory details, check-out the TC-23.

Revenue Snapshot - March 2021 (FY21)

TC-23 Revenue Summary (Period 8, FY 2021)

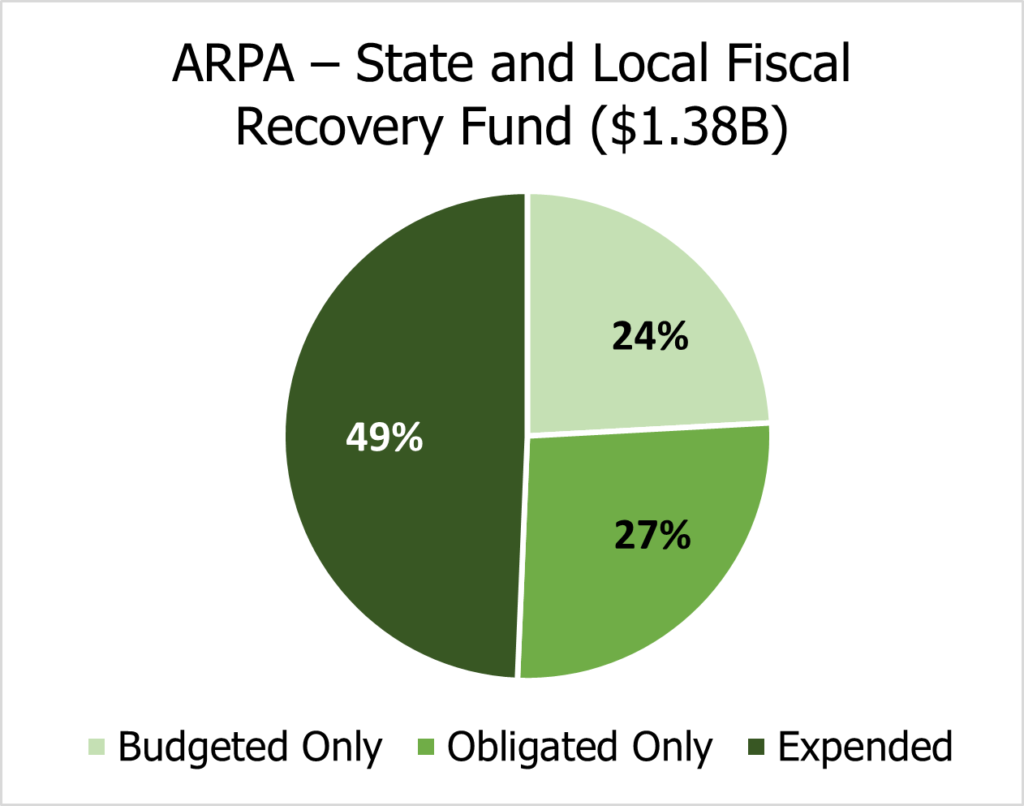

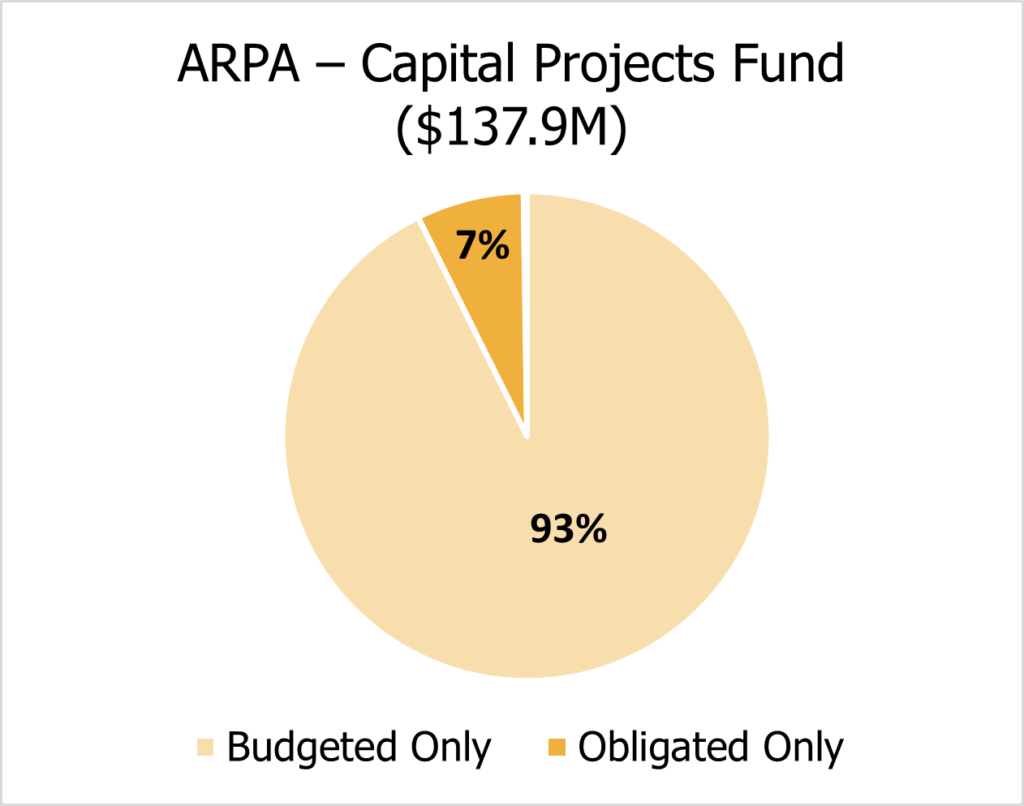

What Does the American Rescue Plan Act Mean for Utah?

On March 11th, Congress enacted the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021, the third (and likely final) round of stimulus funding related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the total $1.9 trillion in Federal aid, the Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst (LFA) estimates that over $8.3 billion will make its way to Utah in the forms of payments to state and local governments, targeted agency grants, enhanced unemployment benefits, and individual stimulus checks. The financial impact of APRA in Utah is somewhere in the middle of the previous two stimulus packages passed by the Federal government in 2020. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) and Families First Corona Virus Response Act (March 2020) brought in roughly $13.6 billion in aid to Utah, and the Consolidated Appropriations Act (December 2020) infused approximately $4.3 billion to the Beehive State.

The LFA summary of the stimulus package includes information about funding distribution to Utah by recipient, along with permissible uses. Details on timing constraints, matching requirements, and other specifics can be found in the companion table. This summary brief will be updated as additional details are made available. Provided data is preliminary, and is subject to change as federal agencies responsible for managing the programs issue further guidance.

The reports referenced in this post can be found below:

Initial Summary of the American Rescue Plan Act

American Rescue Plan Allocations to Utah (Companion Table)

Legislators Alter the Trajectory of Taxation in Utah

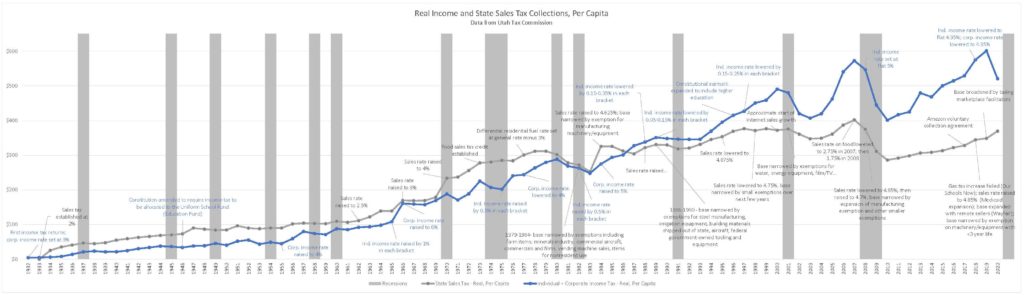

Have you ever laid awake at night wondering ‘when did Utah start collecting sales tax?’, ‘was income tax always earmarked for education?’ or even ‘I wonder if there’s a lag between recessions and income tax collection?’ If you have, you may be a fiscal analyst at heart.*

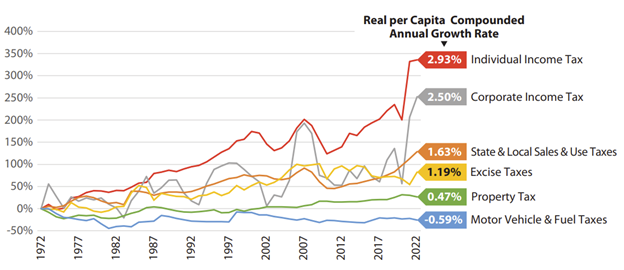

The answer to all these questions and more is in the Legislative Fiscal Analyst diagram of the complete history of income and sales taxation in Utah. This nerd-worthy graph is based on the Utah State Tax Commissions regularly published History of the Utah Tax Structure. The chart shows policy changes superimposed on historical trends for real, per-capita income and sales tax revenues. Gray vertical bars represent periods of recession in the economy, such as the Great Recession beginning in 2008. (Note: 2020 figures are approximate, as they are based on population and Consumer Price Index forecasts.)

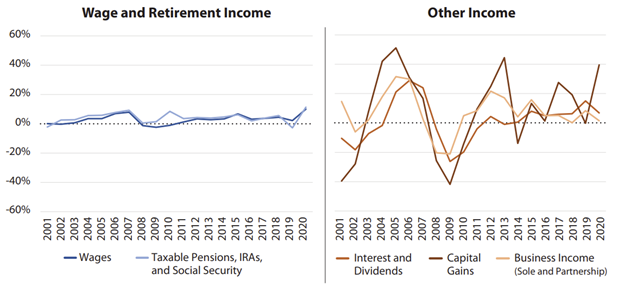

Presenting the tax revenue data this way allows legislators and constituents to observe how individual policy choices have impacted the trajectory of sales and income taxes. Outside factors (including things like consumer spending patterns) have also influenced changes in tax revenue. It is noteworthy that over time income tax revenue has proven more volatile than sales tax. That volatility has been partially spurred by policy changes. Another key takeaway from the chart is that starting in the early-to-mid nineties, a growth differential between the two taxes began which has accumulated over time. This is important because until recently, income taxes in Utah were earmarked only for education in Utah.

In November 2020, voters passed Constitutional Amendment G, which in the medium-term makes the growing gap between income tax and sales tax a bit less worrisome. The amendment gives appropriators the flexibility to use income tax revenue for programs that benefit children and individuals with disabilities, in addition to public and higher education. In the 2021 General Session, this allowed legislators to shift nearly $456 million one-time income tax revenues to these newly approved uses in FY 2021 and FY 2022. In-turn, this freed up General Fund revenues which allowed the state to invest tax windfalls associated with the pandemic in roads, transit, parks, and recreation. The one-time funding swaps will revert to their original designations in the FY 2023 base budgets. However, Amendment G is only a partial solution to tax modernization in Utah, as demonstrated by one-time changes made by the 2021 Legislature.

Legislators also passed three bills during the 2021 General Session that set out to address the revenue disparity, and also aim to reduce the income tax burden on families, military, and senior citizens. Senate Bill 153, which changes dependent exemptions, reduces an estimated $54.9 million ongoing in income tax revenue. Senate Bill 11 eliminates taxes on military retirement pay, reducing income tax payments for certain individuals by an estimated $24.6 million ongoing in aggregate. Finally, House Bill 86, which reduces tax collected for certain social security income, is estimated to reduce Education Fund balances by $18.3 million ongoing.

The Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst will continue to update this chart as new information is available, for as American writer and educator John Gardner said, “history never looks like history when you are living through it.” (At least not until it’s been summarized in a nifty line graph.)

*And you should know we are hiring.

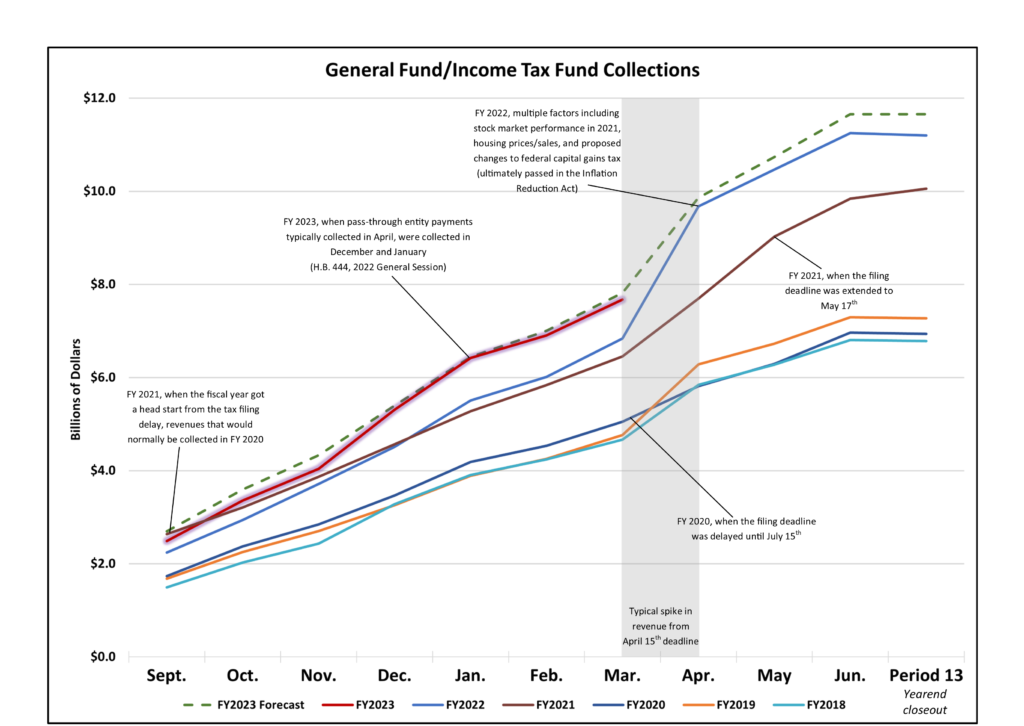

Revenue through Third Quarter Lags Projections

Utah's General and Education Fund revenue collections for the first nine months of fiscal year 2021 slightly lag projected full-year growth rates. Through March, General and Education Fund collections have grown by 26.3% compared with an expected 27.9% for the fiscal year* as a whole.

Should this -1.6% differential remain unchanged in the remaining three months of fiscal year 2021, Utah would have a $148 million General and Education Fund deficit at fiscal year-end. However, legislative economists expect collections will accelerate in the next three months as corporations and individuals pay income taxes in April and May. This is in contrast to last year when final payments weren't made until July 15 - after fiscal year 2020 ended.

Transportation Fund revenue collections for the first three quarters of the year are currently up only 2.8%, significantly trailing behind full-year projections of +5.6%. However, last year fuel sales in the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2020 dropped due to stay-at-home orders. Economists expect the year-over-year difference in motor fuel collections will accelerate in the next three months.

*Utah's fiscal year runs from July 1 to June 30.

For more detail, see our regular publications at the links below:

April Revenue Snapshot FY 2021

TC-23 Revenue Summary (Period 9, FY 2021)

What's in Store for the 2021 First Special Session?

On Monday, May 10th, 2021 the United States Treasury released additional guidance related to the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). While there are still many unknowns, we now know:

1. Utah will receive its state allocation in two 50 percent tranches, with half arriving this May and the remaining in May 2022.

2. Which industries can be considered “impacted” by the pandemic, for the purposes of receiving aid from these funds. Tourism, travel, and hospitality industries are considered impacted, as well as other industries that have experienced comparable negative economic impacts from the pandemic. The guidance gives the example of the revenue decline of 24 percent and the employment decline of 17 percent nationally for the leisure and hospitality industry, as a benchmark for whether other industries might be considered “impacted” and thus eligible to receive assistance from ARPA funds.

3. How state revenue loss should be calculated to determine the extent of which ARPA funds may be used for revenue replacement. Utah will calculate a baseline for anticipated pre-pandemic revenue using fiscal year (FY) 2019 as the starting point and applying a growth adjustment of the greater of 4.1 percent per year or Utah’s average annual general revenue growth rate from FY 2016 to FY 2019. This baseline will be compared to actual revenue collections, and the difference may be considered revenue loss, and thus be filled using ARPA funds.

On Wednesday, May 19th, the Legislature expects to convene for a Special Session in which the state will formally accept these ARPA grant funds from the Federal Government. While total allocations have not been finalized, initial estimates are that Utah will have $1.65 billion to appropriate under both the State Fiscal Relief Fund and the Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund. Of that amount, only a portion will be appropriated during the Special Session, for the State’s most pressing needs. The Utah Legislature will spend the interim deciding on the best uses of ARPA funds for the state, waiting for the 2022 General Session to distribute remaining ARPA funding, once final allocations and guidance have been issued. The Executive Appropriations Committee has drafted a menu of allocations that the state can use to guide spending of this massive fiscal stimulus package on permissible uses.

Update 5/20/2021: During the 2021 First Special Sesssion, the Legislature passed Senate Bill 1001 Appropriations Adjustments, which appropriated funding from the American Recovery Plan Act (among other things). An index of S.B.1001's General and Education Fund, ARPA and Utah Capital Investment Restricted Account adjustment is available here.

Sales Tax Exceeds Expectations, Income Tax Still Boosted from 2020 Filings

On May 14th, the Legislative Fiscal Analyst and Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget released their Revenue Snapshot summary, based on the Tax Commission’s TC-23 revenue summary for May of 2021. Growth to all state funds slightly exceeded projections, posting a 28.3% growth rate through 10 months of the Fiscal Year (FY).

From all sources, the General Fund grew 8.5 percent over May of FY 2020. Of that growth, sales and use tax was the largest contributor, with a 14.4 percent growth rate over the same time last year. Sales tax reported in May reflects sales which took place in the month of March, that were collected in April. This bump may be attributed tourism expenditures over spring break (especially in contrast to March of 2020), in addition to issuance of the final round of individual stimulus checks. Collections from ‘All Other Sources’ (including Oil and Gas Severance Tax, Court Fees, and others) were down -15.0 percent from FY 2020, but were well within the forecasted range.

Education Fund collections are still inflated primarily due to delayed income tax payments, which moved the tax filing deadline from FY 2020 to FY 2021. All other sources to the Education Fund (including Mineral Production Withholding tax) are down -21.6 percent but fall within the expected range. Corporate earnings have increasingly exceeded projections, this month posting an 89.5 percent growth rate over May 2020. Next month’s revenue summary may see an even larger disparity for Education Fund collections between fiscal years, as this year’s final tax payments (due May 17th) are collected and compared against FY 2020 figures. Similarly, the Transportation Fund (which posted a 3.9% growth rate) may see accelerated growth to close the year, as earnings are compared to revenues collected during the stay-at-home orders of spring of 2020.

To celebrate Tax Day, on May 17th the Legislative Fiscal Analyst released updated Consensus Revenue estimates. These latest estimates build on the adopted revenue forecasts from February 2021 adding changes made by the Legislature during the 2021 General Session, including tax law changes and appropriations from certain restricted accounts that impact general fund revenues.

The reports referenced in this report are available at the links below:

TC-23 Revenue Summary (Period 10, FY 2021)

Revenue Snapshot – May 2021 (FY21)

Economists Warn of Inflationary Pressure as Surplus Trickles In

On Monday, June 14th, the Tax Commission released their TC-23 revenue summary, detailing collections through period 11 of the 2021 Fiscal Year, along with the Revenue Snapshot produced by the Legislative Fiscal Analyst and Governor’s Office economists. In stark contrast to June of 2020, when the legislature passed appropriations bills reducing ongoing budgets, it appears this Fiscal Year will end with revenues in certain categories exceeding annual projections.

The General Fund, fueled primarily by sale and use tax, is up 10.5 percent over the same time last year. Since March, the sales tax growth rate has accelerated, increasing from 10.3 percent growth in February to 16.5 percent growth in May. This trajectory may coincide with federal stimulus actions, and perhaps reflect an increase in consumer confidence as pandemic restrictions are reduced.

The Education Fund posted a 60.6 percent growth rate over the same collection period for FY 2020. Two factors have heavily influenced individual income tax growth: federal stimulus activities and amended tax filing dates. Federal stimulus has had a positive impact on personal income, which makes comparison to previous years (even pre-pandemic) challenging. Second, the current Fiscal Year collections include 2020 and 2021 tax filings and are being compared to FY 2020 in which no individual year-end tax filings were collected. Additionally, Corporate Tax revenue has increased by nearly 95.0 percent over last year, indicating sharp increases in corporate income.

While the outlook for the end of the fiscal year is positive for Utah (with an expected budget surplus) the increased revenue may be bittersweet. Federal stimulus which has influenced upward growth in each of the state funds may also be contributing to inflationary pressure, which could result in the nominal growth measured in these reports less impactful.

The reports referenced in this post are available at the links below:

TC-23 Revenue Summary (Period 11, FY 2021)

Revenue Snapshot - June 2021 (FY21)

Federal Intervention Drives Unpredicted Growth in Preliminary FY 2021 Year-End Tax Collections

According to the Utah State Tax Commission’s preliminary 2021 fiscal year-end TC-23 revenue summary and an accompanying Revenue Snapshot from the Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst and the Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget, preliminary data show total state revenues up 30.5 percent at the end of FY 2021 compared to FY 2020. This increase surpasses economists’ expectations and indicates strong economic growth coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic and economic downturn. However, there remains considerable uncertainty regarding the extent to which unprecedented federal stimulus throughout the fiscal year has buoyed revenues and created a one-time bolster effect that will not aid revenues moving forward. All year-end numbers are tentative at this point pending final accounting adjustments. Such adjustments could include deposits to rainy day funds and allocations to earmarked restricted funds, which may decrease final General and Education Fund numbers.

General Fund collections grew 16.5 percent on a year-over-year (YoY) basis, compared to a target of 9.6 percent. Taxable sales are up 20.0 percent YoY, with some of the hardest-hit sectors experiencing dramatic bouncebacks, such as transient room taxable charges up 246 percent and restaurant taxable charges up 47.7 percent YoY. Two rounds of stimulus checks, coupled with pent-up demand being released as the economy gained steam, bolstered General Fund collections in FY2021.

Education Fund collections grew by 41.3 percent YoY, compared to a target growth rate of 27.9 percent. While individual income tax grew by 53.3 percent, corporate income tax hit an astonishing 108.1 percent YoY growth rate. Once again, the effect of federal stimulus legislation is at play in Education Fund collections; loans enabled businesses to keep employees on their payrolls, and unexpectedly high consumer spending likely aided income tax collections as well. Additionally, due to the delay in the income tax filing deadline in 2020, the YoY growth rate does not include total 2020 collections, and so should be interpreted cautiously.